As a self-proclaimed tea nerd, it’s quite an oversight on my part that I haven’t delved into how deeply Pleiku’s identity is steeped in tea until now. Tea production in this region is a cornerstone of Pleiku’s identity today, with roots tracing back to the era of French colonization.

Setting the Scene

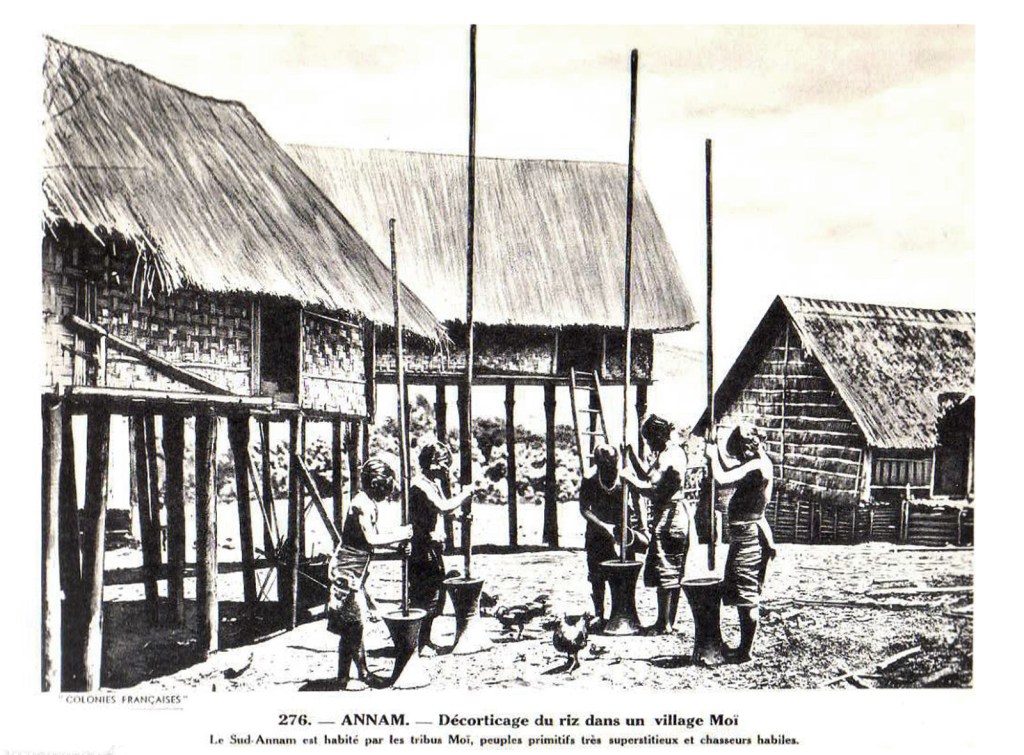

Our tale begins in 1925, over three decades since Vietnamese emperors yielded to French colonial rule. Despite this shift, the Tay Nguyen Plateau remained a wild frontier, though the French – themselves recovering in the aftermath of World War I – were slowly making inroads. At this time, the region was largely autonomous, with ethnic Vietnamese sparsely scattered amidst the predominantly Montagnard population. In this year the infamous Pleiku Prison was constructed to help maintain French authority by hook or by crook.

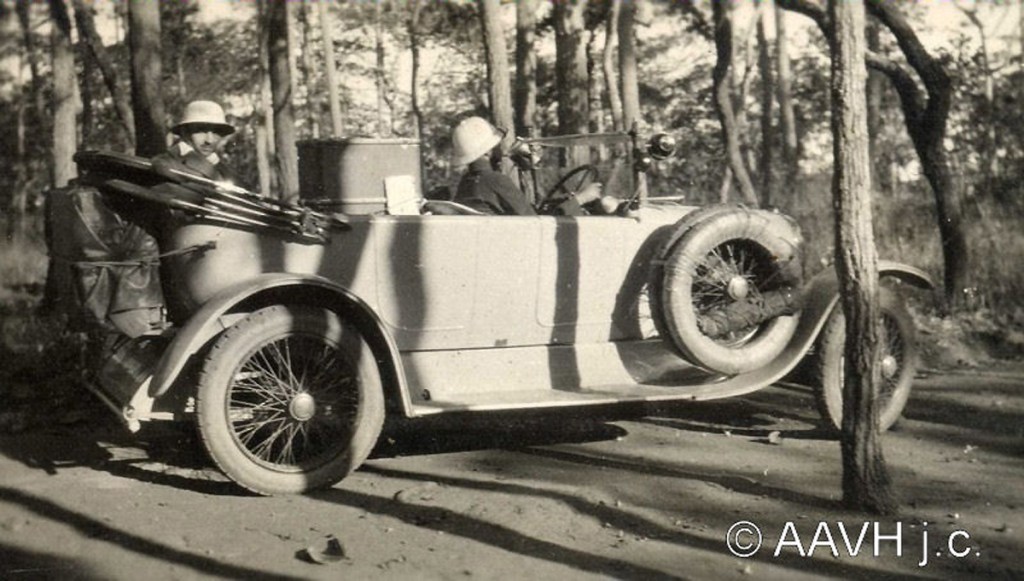

Nature reigned supreme in this domain, with rivers teeming with crocodiles and jungles prowled by tigers and pythons. Within this daunting landscape, pith-helmeted Frenchmen boldly embarked on endeavors to establish tea plantations and impose their version of “civilization” upon the wild highlands.

The Moï province of Kontum occupies, in Center-Annam, a medium altitude plateau (600 to 900m) whose richness in “terres rouges” tempted so many colonists that the General Government of Indochina considered it necessary to carry out a preliminary investigation on the state of health of agricultural operations in this region. The local population being relatively sparse and having reduced working capacities, it was likely that they would quickly need to call on imported labor whose fragility is common knowledge in colonies… The first priority was therefore fixing the climatic characteristics and pathology of a region whose development was going to require the immediate mobilization of thousands of coolies from Tonkin or the more populated lowlands. – “LE PALUDISME [malaria] DANS LA PROVINCE MOI” Archives des Instituts Pasteur d’Indochine 1928

In fact, the region has only been open to colonization through effective pacification and the development of roadways since 1924 under the leadership of M. le Résident Fournier. In 1926, more than one hundred thousand hectares of land were, after prospecting, requested in concession by French and foreign planters.

As we know, the Moi people do not have much sympathy for immigrants. Since a large number of immigrants are employed in certain plantations, this often leads to conflicts and ends in regrettable ways. This is how the minorities attacked a bus on the road: Three passengers were killed by poisoned arrows and several others were injured. Acts of sabotage were also carried out on a rubber plantation (referring to the Dak Joppau plantation in An Khe – NQH). After these events, a militia was sent to suppress the rebels, but the Montagnards fled and retreated into the forest. As punishment, it was decided to use planes from Bien Hoa (NQH: newspapers wrote from Bien Hoa according to the information they had) to suppress them. A military squadron was assigned to bomb several villages of the Montagnards.” ( Une révolte chez les Moïs , 1929, p.11830).

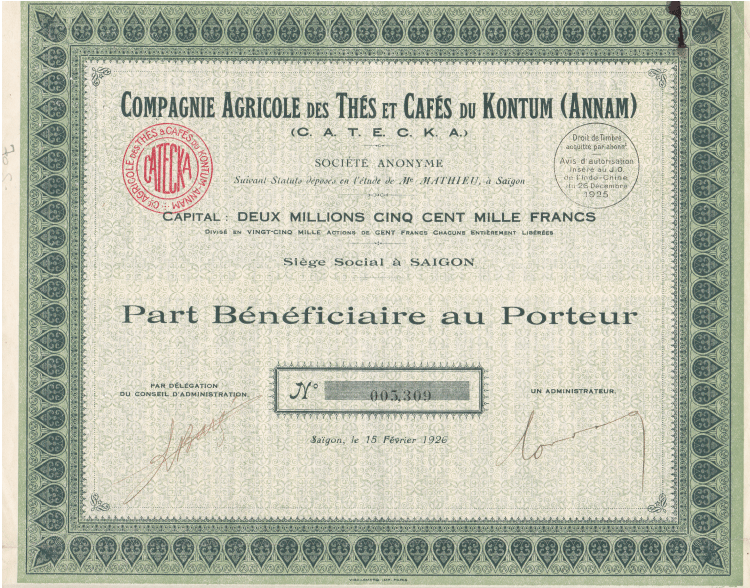

CATECKA (Chè Bàu Cạn)

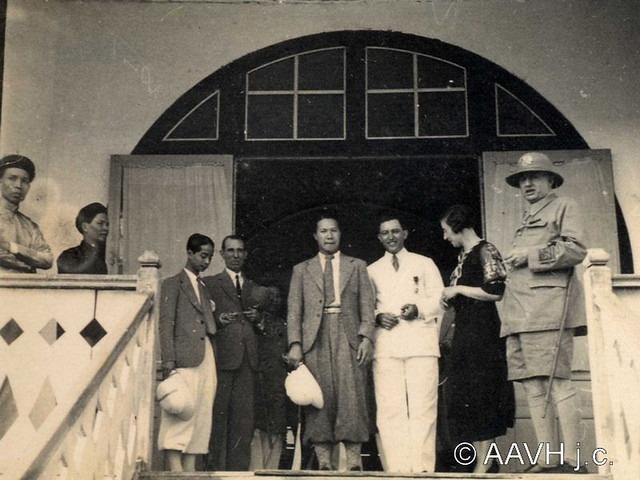

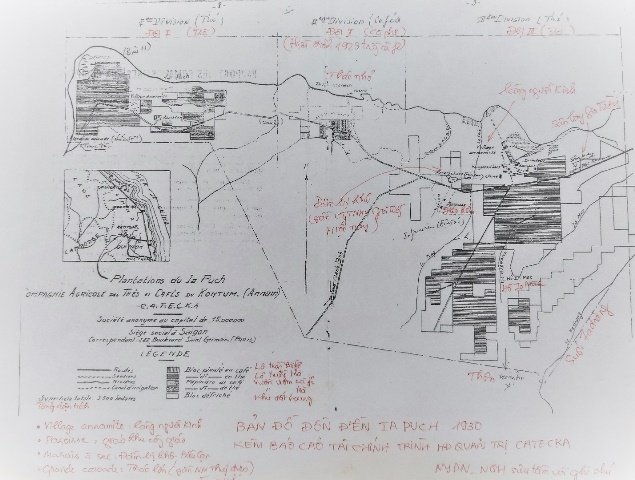

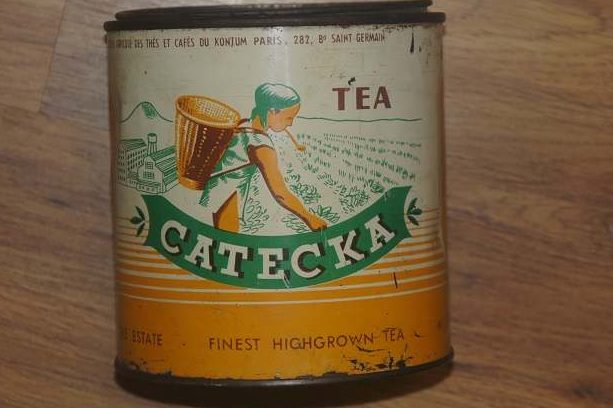

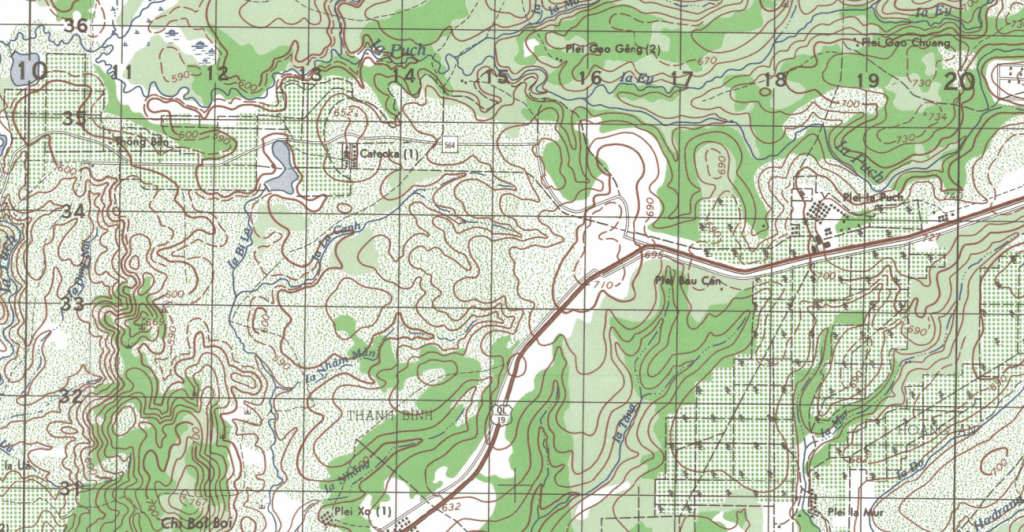

Amidst this backdrop, the most renowned tea plantation of the era emerged: CATECKA (Compagnie Agricole des Thés et Cafés du Kontum Annam) situated near Bàu Cạn and established in the same pivotal year of 1925. Thanks to the Gia Lai Museum for some wonderful resources (1, 2, 3) so I didn’t have to dredge through too much French for my research.

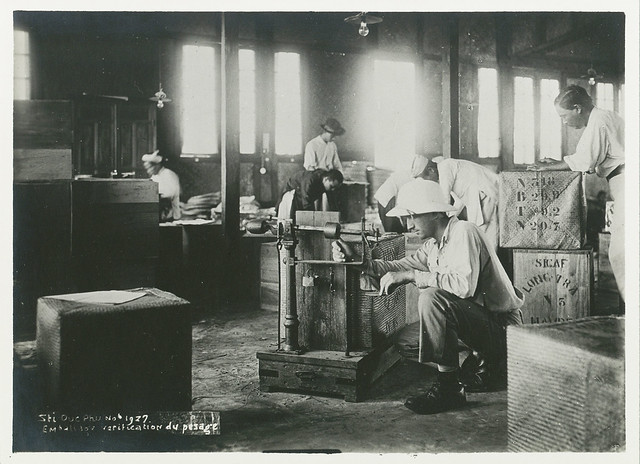

Catecka, Bau Can tea department, employed about 800 coolies – source

The harsh labor regime at Bau Can plantation made the material and spiritual lives of workers extremely difficult and miserable, with poor food, poor health, and constant illness. Plantation workers were severely exploited, beaten, berated, fined, and female workers were raped. They also poisoned workers with alcohol, tea, opium, and gambling, causing them to fall into debt. Once they borrowed money, the debt would be passed on to their children. Entire lives were tied to the plantations; slaves to the French owner.- Gia Lai Museum

Fast forward to 1962, where the acronym has seamlessly transitioned into the word “Catecka” (as seen on the map). Our next insightful source comes from David Noble‘s fascinating book “Saigon to Pleiku.” In his memories, during his visit with the US military, Noble met the then manager, a Frenchman named Claude Salvaire. Notably, Catecka was then a supplier of black tea leaves to none other than Lipton Tea.

“There, under the influence of gin and tonics, he regaled us with stories, his favorite being about his tiger hunts on the property. Trophies on the wall bore evidence of his shooting skill. His hunting method, he told us was to tie a live goat to a tree out in tiger territory and wait in a blind through the night. When he heard the sounds of a tiger killing the goat, he would shoot it” – David Noble

It’s fascinating to consider a Frenchman like Claude overseeing a business in what essentially was the wild west, particularly in the aftermath of the Điện Biên Phủ conflict. Undoubtedly, it must have been a chaotic and unpredictable era.

“These French are a weird crowd. They are the dregs of the French Empire who have not wanted to return. As far as I’m concerned, anyone who would choose to remain in this country must have a pretty damned good reason for not going home. And most of them do. Either they ran into big trouble in French and sought refuge in Indo China long ago or they were adventurers and scoundrels in the Foreign Legion who deserted when the chips were down. They have free travel throughout the country since the VC [Viet Cong] don’t bother with them except to tax the plantations. Many of them have very colorful and unusual pasts.” – David Noble, 19th of February 1963

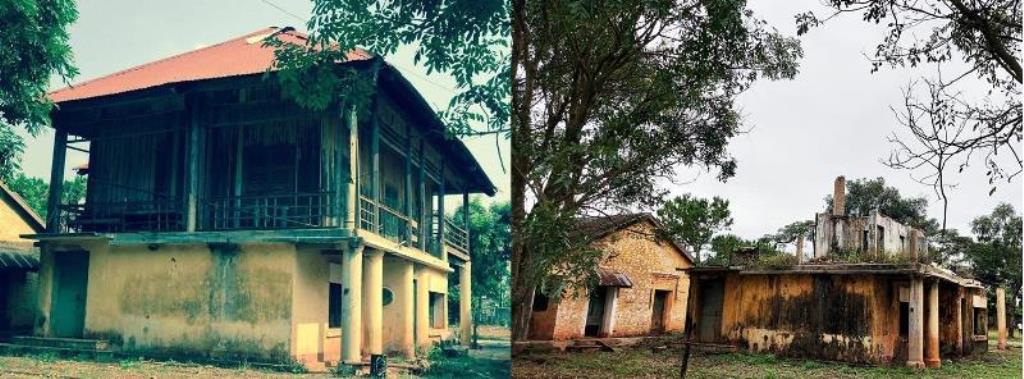

“Not a quarter-mile through the tea bushes from Brown’s tents stood a lovely white colonial mansion. The French plantation manager lived there, and if you strolled the road you caught glimpses of young women in bikinis taking the sun beside the swimming pool. The mansion had been neither mortared nor attacked the night before. Army intelligence said the French owners paid the Viet Cong a million piasters a year in protection money and paid the Saigon government three million piasters a year in taxes. The plantation billed the U.S. government $50 for each tea bush and $250 for each rubber tree damaged by combat operations. Just one more incongruity.” – We Were Soldiers Once…and Young– writing about 1965, published 1992

The legacy of the Catecka tea plantation endures to this day under the management of CTCP Chè Bàu Cạn. With a sprawling 450-hectare plantation, they continue to produce approximately 2,600-2,800 tons of tea annually (source). The name “Catecka” persists in some of the branding even in 2024, serving as a poignant reminder of its storied past.

“There was a huge tea plantation that was very close to the base camp and that was an area where the enemy could hide-out very easily. And it was a dangerous area” – Frank Farrell (2:20)

Links

STI Biển Hồ Chè

According to the manager, there are 600 women and 150 groups of tea pickers each day – From Bao Dai’s visit in 1933

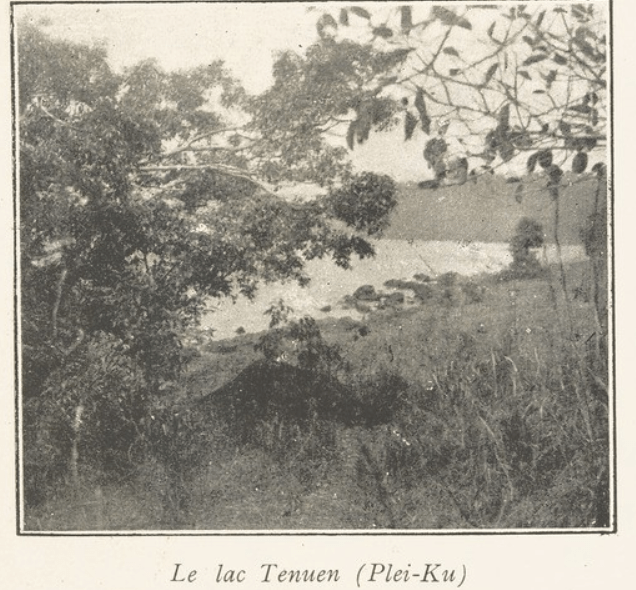

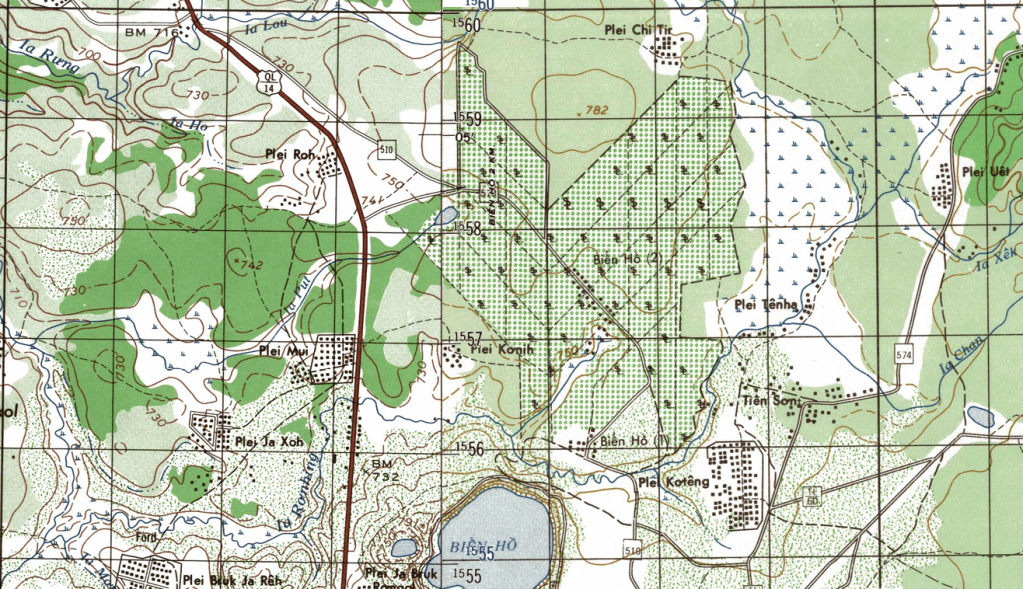

Biển Hồ Chè, perhaps more renowned today than Catecka for it’s tourism, shares a similar inception story. Established in 1925 under the unfortunate name STI (Société des Thés de l’Indochine), both companies capitalized on the expertise of a visiting Dutch Engineer named Van Mannen to kickstart their operations, particularly in the processing of black tea after harvesting. According to the newspaper L’Éveil économique de l’Indochine (Indochina Economic Awakening), issue dated January 6, 1929: by the end of 1927, Pleiku Bien Ho tea plantation had planted 500 hectares of tea trees (on an area of application is 2,810 hectares) at a cost of about $1,050 per hectare.

Sources about Bien Ho Che are much sparser during the war compared to CATECKA. However it was mentioned in 1969 meaning it was probably functional, or at least not totally destroyed.

Bien Ho Che has become one of the main tourist destinations in Pleiku. Visitors flock not only to capture photos amidst the rows of low tea trees but also to admire the towering pine trees that line the roads, dubbed “100-year-old pine trees” by locals. Visitors can enjoy a freshly brewed cup of tea at one of the charming roadside cafes situated right beside the very trees that yielded the tea leaves.

Today the plantation is managed by CTCP Chè Biển Hồ – find them in the Yellow Pages (a bit of history in itself!)

The story isn’t all tea and biscuits; these plantations left an indelible mark on the natural environment and the indigenous way of life. Yet, after delving into their history, there is something to admire about their resilience. Rising from the wilderness and weathering two tumultuous wars, they’ve emerged as beacons of tranquility today. Despite their rocky past, they beckon visitors to escape the urban chaos and find solace in Pleiku’s serene landscape. I think these plantations serve as a testament to Pleiku’s ability to acknowledge its past while embracing progress.

Dak Doa

There was another plantation at Dak Doa (in modern Dak Krong). I’m currently researching so if you’re interested, watch this space. If you can’t wait you can read the Vietnamese for yourself, or the french.