The dirt road gave way abruptly to a stretch of wet concrete drying under the sun. Nearby, men were clearing up after a days work. A glance at Google Maps suggested I was only 1.5 kilometers from my destination, so I decided to park my moped on the verge and began walking.

From behind a hedge, an old woman called out, “Where are you going?”

“Plei Ring,” I answered.

She shook her head. “Plei Ring’s been under the lake for years. The road only leads to the water.” I replied that I think there is a monument there. “There’s no such monument” she said.

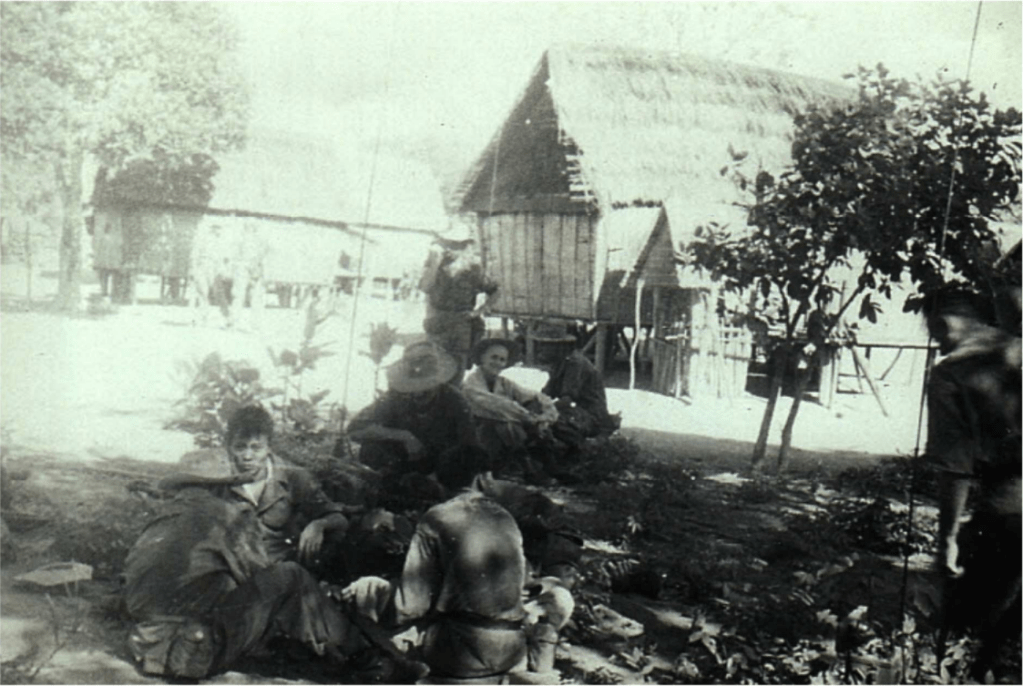

Her words lingered in my mind as I made my way forward, determined to find what I’d come for. While researching for my blog I came across the Battle of Plei Ring. I initially found references only in Vietnamese sources and found out there was a stele erected in the area to commemorate it – that’s where I was headed now. At first, I thought western records of the battle were nonexistent. It wasn’t until I closely studied old maps that I realized the discrepancy: where Vietnamese sources spell it Plei Ring, western accounts use Plei Rinh. This subtle difference highlights the care required when researching history so as not to miss important sources.

The Battle of Plei Ring involved one of the most formidable units of the French forces in the First Indochina War: Group Mobile 100 (GM100). Its core consisted of battle-hardened veterans from Korea, renowned for their valor in battles like Chipyong-ni, Wonju, and Arrowhead Ridge. The unit was bolstered by indochina troups in a process the french weirdly called « jaunissant ». After the Korean cease-fire in July 1953, this elite force was transferred to Indochina and formally reorganized as Group Mobile 100 on November 15, 1953. The G.M.s were designed as self-sustaining motorized regimental task force unit modelled on the U.S. Army’s World War II regimental combat teams. The G.M.s typically consisted of three infantry battalions with one artillery battalion, along with elements of light armor or tanks, engineer, signal and medical assets, totaling 3,000–3,500 soldiers

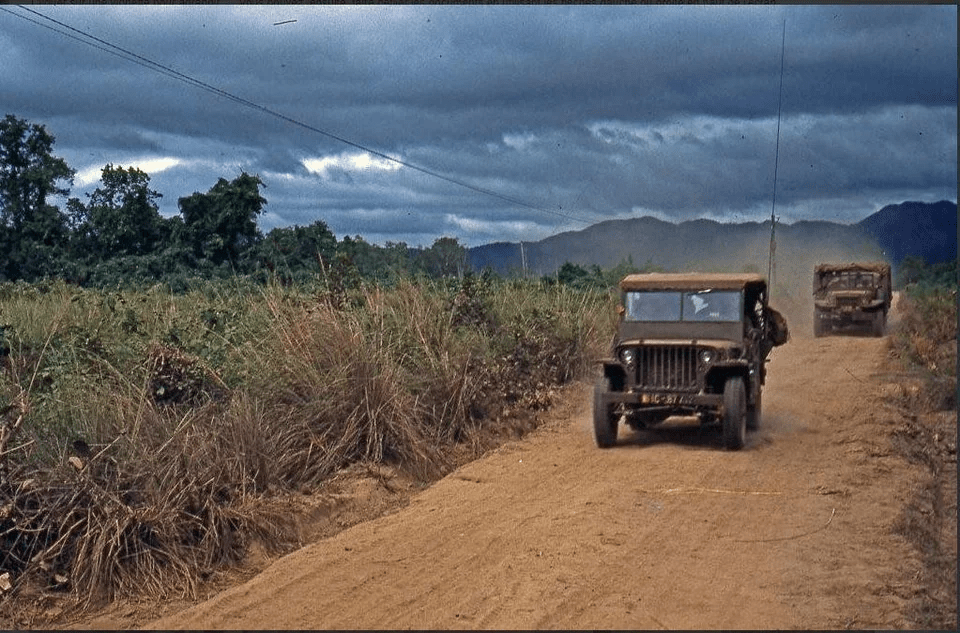

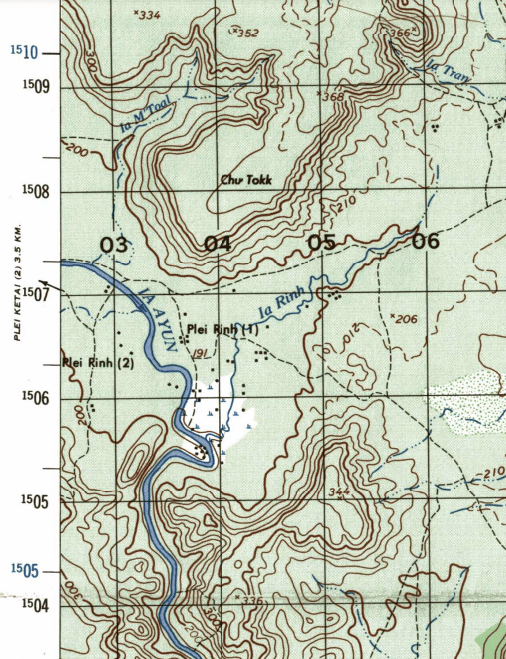

While up north things were heating up at Điện Biên Phủ, this veteran unit was tasked with securing strategic locations in the Central Highlands, after being battered around by the Viet Minh from Dak To down to Dak Doa, they moved to dig in at Plei Ring in the Ayun Valley, which was on what the French referred to as the “Pleiku-Ban Me Thot axis”.

The Ayun Valley is a striking contrast to the otherwise flat terrain of the Pleiku Plateau. From the ground, the plateau appears unbroken until the valley suddenly reveals itself—a vast, hidden expanse carved into the land. I was unaware of its existence during my first years in Pleiku until studying detailed 1:50,000 maps revealed the contours of this dramatic feature. Its natural concealment, reminding me of a ha-ha, probably made it an ideal approach for Vietnamese troops to advance undetected, likely influencing the strategic placement of the Plei Ring outpost.

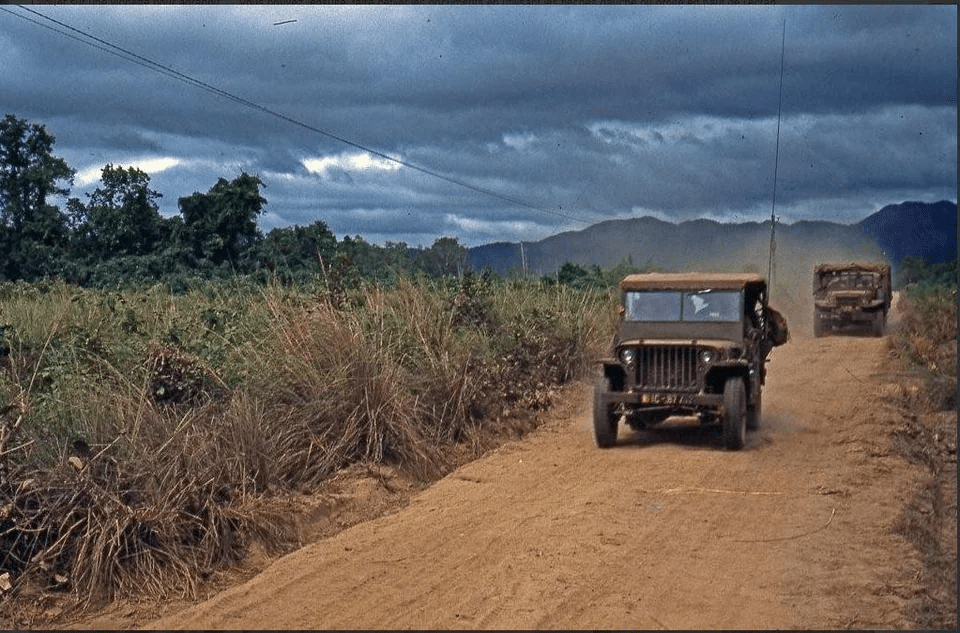

“At that time, my unit operated in the southwest of Pleiku town, but we often marched through Ring village… Plei Ring post was located in the middle of a fairly flat valley. The post was triangular in shape, surrounded by sparse barbed wire fences, thatched roofs, about 15m in height, and they added patrols and guards. Many of my comrades on the march unfortunately died here.” – Ngô Thành (source)

On March 21, 1954, the Viet Minh’s 803rd Regiment launched a surprise attack on GM100 at Plei Ring. Employing rapid and decisive tactics, they overwhelmed the French garrison in just two hours. This victory not only disrupted the French defenses in the region but also boosted the morale of Viet Minh forces across other theaters of the war.

G.M. 100 setup camp at a small remote outpost called Plei Rinh. There they were viciously attacked again. First came the violent mortar fire, then the concentrated fire of rifles and machine guns. The CP was targeted and hit. Suddenly came the onrushing wave of black clad Viets screaming “Tien-len!” The post soon burst into flames as the Recoilless cannons peppered the grounds. All was sound, fury, and chaos. Then, as quickly as they had appeared, the soldiers of the 803rd disappeared. The toll was heavy on the French… G.M. 100 had been severely crippled. But not beaten. – source

The French reported over 250 casualties, with the Vietnamese claiming to have neutralized nearly 1,000 enemy soldiers and destroyed more than 200 vehicles. Though figures vary, the significance of the Viet Minh victory is undeniable. It disrupted French control in the area and dealt a blow to their morale during a critical phase of the war. The GM100 would retreat to Pleiku and later move to An Khe setting the stage for their ultimate downfall at the (in)famous battle of Mang Yang pass.

Today, the site of Plei Ring village itself lies beneath the waters of Ayun Hạ Lake, created by the Ayun Hạ Dam in the 1990s. A small commemorative stele near the lake honors the sacrifices made. As I followed the newly paved road called “the French pass” into what was once the fertile Ayun Valley, now transformed into a reservoir, I imagined the events that unfolded here decades ago—the place is now makes a good location for a peaceful hike in the native dipterocarp forest.

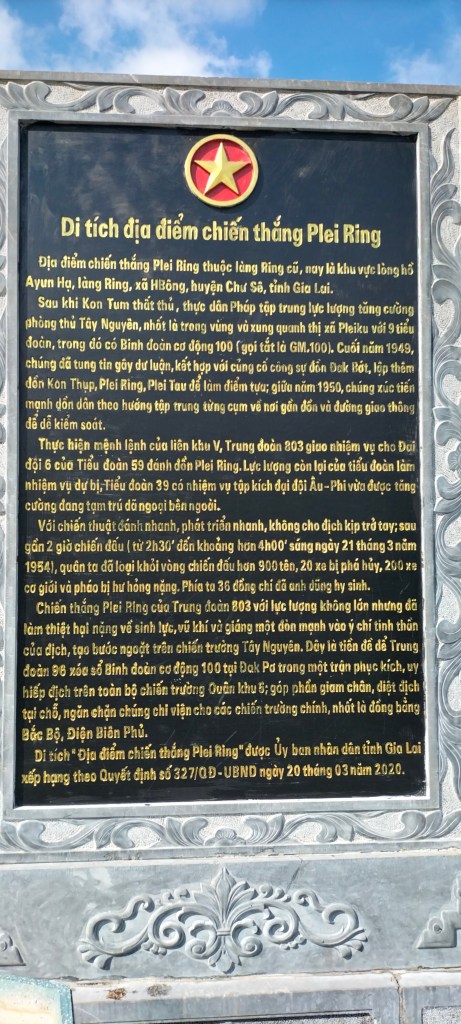

Plei Ring Victory Site Relic

The Plei Ring victory site belongs to the old Ring village, now the Ayun Ha reservoir area, Ring village, HBong commune, Chu Se district, Gia Lai province.

After Kon Tum fell, the French colonialists concentrated their forces to strengthen the defense of the Central Highlands, especially in and around Pleiku town with 9 battalions, including Mobile Regiment 100 (abbreviated as GM.100). At the end of 1949, they spread rumors to stir up public opinion, combined with consolidating the fortifications of Dak Bot station, establishing Kon Thup, Plei Ring, and Plei Tau stations as support points; in mid-1950, they strongly promoted the concentration of people in clusters near the station and traffic routes for easier control.

Carrying out orders from Inter-Zone V, Regiment 803 assigned Company 6 of Battalion 59 to attack Plei Ring post. The remaining force of the battalion acted as reserve, Battalion 39 was tasked with attacking the newly reinforced Euro-African company that was temporarily camping outside.

With the strategy of quick attack and rapid development, not giving the enemy time to react; after nearly 2 hours of fighting (from 2:30 a.m. to about 4:00 a.m. on March 21, 1954), our army eliminated more than 900 enemies from the battle, 20 vehicles were destroyed, 200 vehicles and artillery were severely damaged. On our side, 36 comrades heroically sacrificed themselves.

The Plei Ring victory of the 803rd Regiment, although not a large force, caused heavy losses in manpower and weapons and dealt a heavy blow to the enemy’s will to stay awake, creating a turning point on the Central Highlands battlefield. This was the premise for the 96th Regiment to wipe out the 100th Mobile Division at Dak Po in an ambush, threatening the enemy on the entire battlefield of Military Region 5; contributing to reducing and destroying the enemy on the spot, preventing them from supporting the main battlefields, especially the Northern Delta and Dien Bien Phu.

The relic “Plei Ring Victory Site” was ranked by the People’s Committee of Gia Lai province according to Decision No. 327/QD-UBND dated March 20, 2020. – engraving on the stele

Today, Ayun Hạ Lake covers what was once the village of Plei Ring, hiding its stories beneath the water. While the dam and reservoir serve the needs of modern life—powering homes, irrigating fields, and supporting livelihoods—they also submerge the traces of a history. The past may be buried under the water, but the stories are floating around to be found by those who look.

sources

- https://mcoecbamcoepwprd01.blob.core.usgovcloudapi.net/library/ABOLC_BA_2018/Research_Modules_B/Groupemont_Mobile_100/Vietnam_Vignette_The_French_Groupement_Mobile_100_%20Parallel_Narratives.pdf

- https://baogialai.com.vn/tro-lai-plei-ring-post91555.html

- https://www.aamtdm.net/images/stories/histoire/GM100%20Indochine%201954_aamtdm.pdf