This blog post is about a visit I made to Hoàng Đế Citadel in Bình Định, South Vietnam. It’s a 40 minute drive from Quy Nhơn City.

The only respite from the harsh Bình Định sun was inside the tower, though the air inside reeked of guano. Besides, the ornamentation on its flank unnerved me, the crumbling brickwork seemed to form a huge skull.

The air was dry and dusty, the grass wilted, and the only movement came from a few cows and buffalo grazing by the rice paddies down at the foot of the hill. Insects buzzed in the bush. I scrunched up my eyes, scanning the countryside. From my vantage point I could see another tower on a rise about ten kilometres away, orange bricks standing tall through the hazy air. “Well, now I’ve seen it, I’ll have to visit that one too,” I thought. And so the afternoon went, the sun unrelenting as I scrambled up one hill after another, to get up close to the ancient towers that crowned them.

These solitary towers perched atop a lot of hills in the province are the remains of ancient Hindu temples built by the Champa Kingdom. Today, these towers stand among the last visible traces of the medieval kingdom and are iconic symbols in the minds of locals of the lost civilisation. But the towers are not the only traces left. Earlier that day, quite by accident, I had found something that made me see the Champa story in a whole new light.

My trip that spring had begun with a jaunt down to the seaside accompanied by Emma — an old friend, fellow Brit and wonderful mentor from my English teaching days in Pleiku. This time, she had journeyed from Kuwait to catch up with old faces and get some vitamin sea before heading back to England. We’d spent Tết together in the picturesque cove of Bãi Xép, near Quy Nhơn city. Fittingly for this story, the city was decked out in Champa-themed decorations for the Year of the Snake, blending local history with the Chinese zodiac. On New Year’s Eve, we ambled down to the beach to watch the fireworks bloom over the distant city dancing on the waves. Some village children dashed about with firecrackers, their shouts mingling with the bangs, maybe to summon luck for the year ahead.

I didn’t fancy spending too long lounging by the sea. Fresh from a breakup, I wanted to keep my mind occupied. So while Emma stayed to enjoy the sandy beaches, I turned inland alone on a sort of personal pilgrimage. I set off towards the high altitude city of Pleiku on my trusty old 110cc Honda Blade — the farmers’ favourite — planning to stop anywhere that looked interesting along the way.

The first stop, just outside Quy Nhơn, was a pin on Google Maps that had caught my eye. But when I rolled up, it didn’t look like much — a small village snoozing away the hot national holiday; no tourists, no ticket booth, but thankfully no inflated holiday parking prices. The gate was modest, one might mistake it for a local pagoda. However, the pair of weathered elephant statues outside gave a hint that this village had an illustrious past. Because here, I later learned, had once been Chà Bàn citadel (sometimes called Đồ Bàn), the administrative heart of the Vijaya, Champa — and the place where the kingdom’s story came to an end.

I parked the moped and slipped in through a small open gate beside the main entrance. Inside, I found myself alone in a two-hectare grassy field, hemmed in by a wall of large orange stone slabs. A flagpole stood proud in the centre, flanked by a few pagoda-esque structures. It is the sort of place where you might want to stretch out on the grass under a tree with a flask of iced tea and a bánh mì and listen to the birds singing. So that’s exactly what I did (I’d had the foresight to buy a bánh mì Vietnamese sandwich on the road). Off to the east, perched on a low hill outside the tourist zone, I could see a Cham tower watching quietly over the empty field.

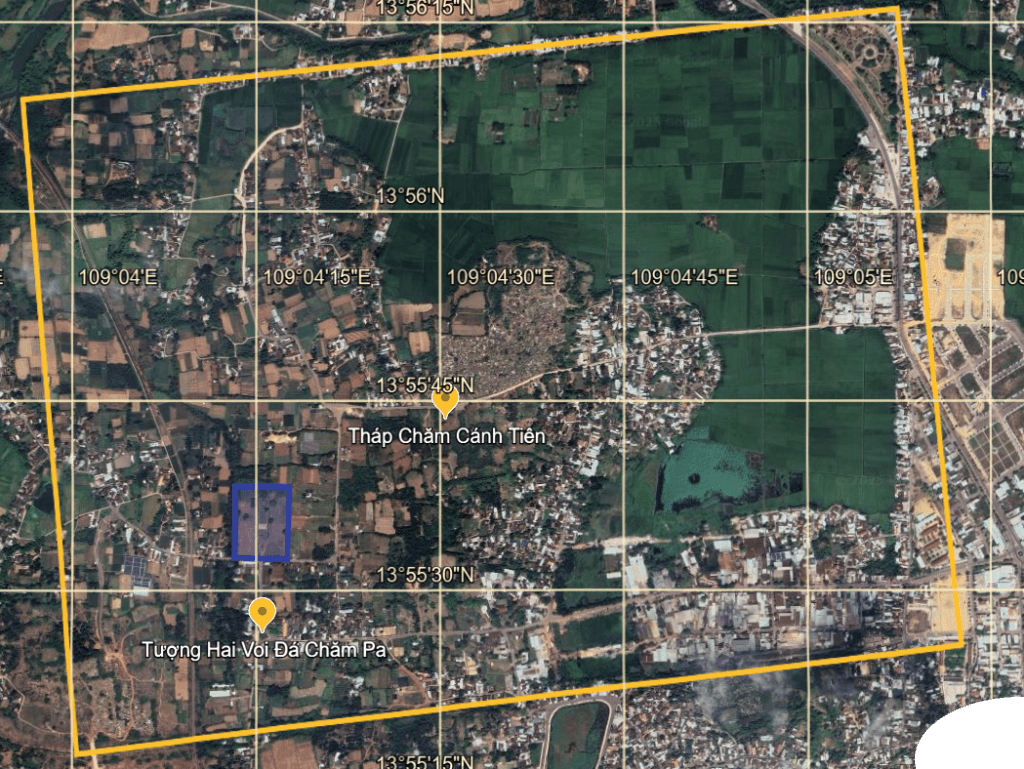

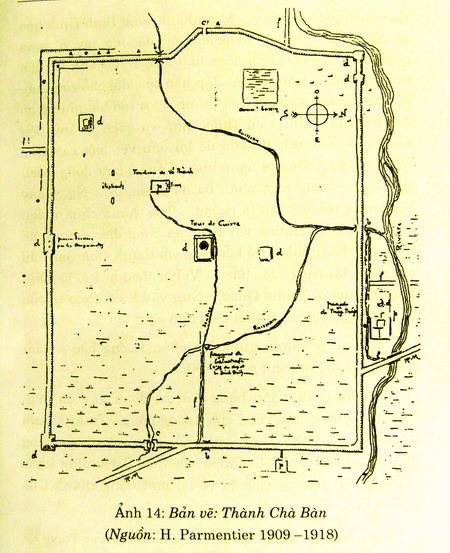

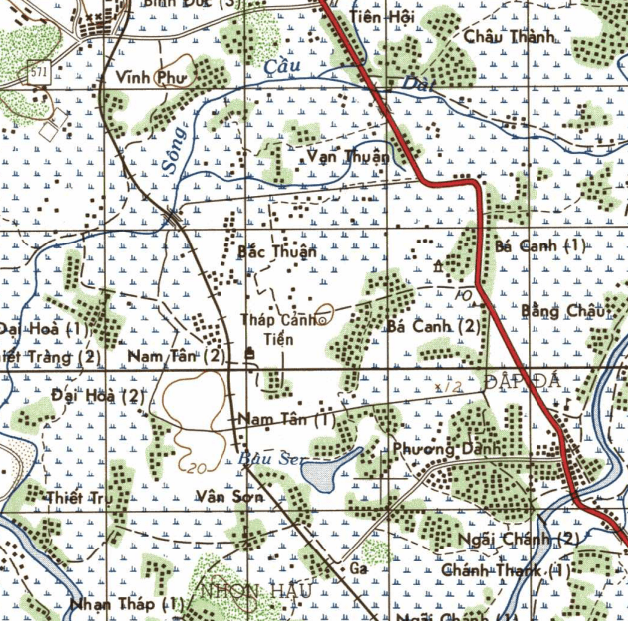

Only later did I learn that this tidy little visitor site is but a postage stamp compared to the original citadel. The ancient stronghold of Vijaya once sprawled across an area of more than three hundred hectares – nearly twice the size of Huế Citadel. A French archaeologist sketched it a century ago, American topographical maps caught it again during the war, and now, with the powers of satellite imagery, I’ve traced its rough outline on Google Earth. As it turns out, that Cham tower, not the flagpole, was the centre point of the original citadel. (source)

What struck me on my second visit was how big the rampart of the outer wall was. I’d totally missed it on my first visit because I’d made a B-line from the main road to the elephant statues but if you approach from the south you pass through a huge mound of earth that reminded me of the unrestored parts of Great Wall of China more than anything – trees growing on it, farms butting against it, roads cutting through it. I estimate the walls must have stood at least 6 meters tall.

Chà Bàn Citadel saw some of the highpoints in Champa history. For example in 1377, Trần Duệ Tông of Đại Việt led an army to attack Chà Bàn in retaliation for several devastating raids Vijaya had perpetrated against Hanoi. Vijaya’s king at the time R’chăm B’nga the Great set a trap for the emperor by feigning surrender only to ambush the Tran forces. In the fray, the Trần Emperor was killed by an arrow. (source)

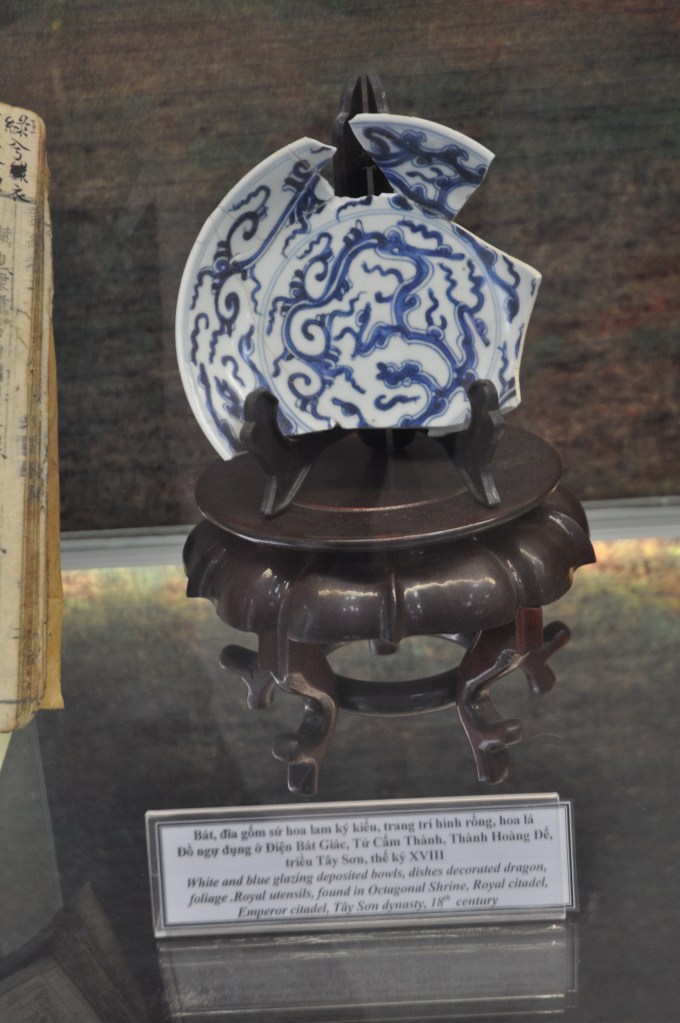

Archaeological finds from the site tell other stories: local pottery fragments, roof tiles, and lion statues. A number of relics are now on display at the Bình Định Museum in Quy Nhơn, while a pair of dvarapalas (buddhist gate guardians) are enshrined at a nearby pagoda, venerated by the locals to this day and having many folk stories surrounding them. I went to see them on my second visit to the area and was amazed by how large they are, they are tall and weight 800kg are quite intimidating.

The citadel of Vijaya stood strong and proud as the capital city, right up until it didn’t. The chronicle: The Complete Annals of Đại Việt, records how during the reign of Vijaya king Maha Sajan (Trà Toàn), a campaign in 1471 led by mighty Vietnamese emperor Lê Thánh Tông sacked the citadel and in doing so brought Champa to its knees. The chronicle doesn’t skimp on the details and is a surprisingly good read. In the quote below you can see evidence of when the Citadel fell with some gory details.

On the 28th [March 19, 1471], the king besieged Chà Bàn citadel …

On March 1 [March 22, 1471] ,Chà Bàn citadel was captured, more than 30,000 people were captured, more than 40,000 heads were cut off, Trà Toàn was captured alive, and the army returned.(Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư pp. 1383-1384)

blue area: outline of Hoang De citadel

source: Lê Đình Phụng, Di tích văn hóa Champa ở Bình Định (Champa Relics in Binh Dinh Province) (Hanoi: Nhà xuât bản khoa học xã hội, 2002).

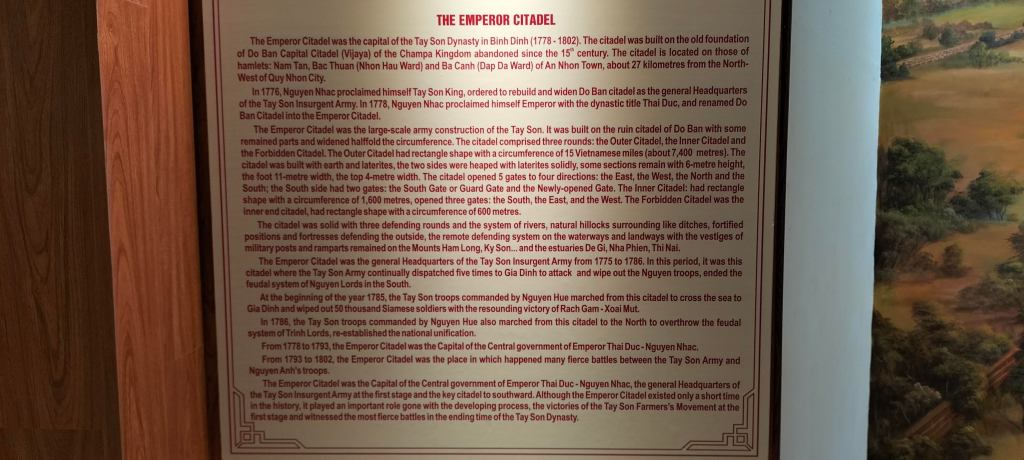

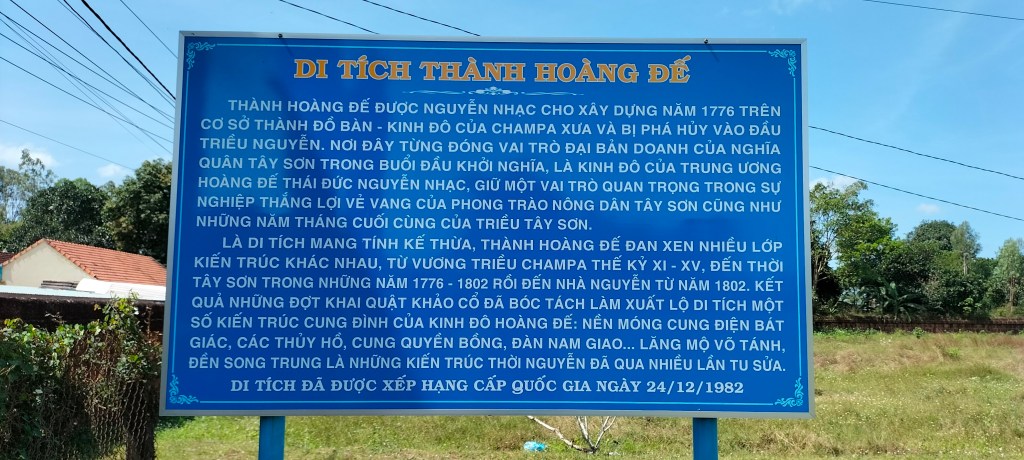

But the story of this citadel doesn’t end with the fall of Champa. In the late 18th century, more than three centuries after Chà Bàn Citadel fell, it found itself swept up in the drama of the Tây Sơn Rebellion.

I’ve already talked in another post about my stop at Tây Sơn Thượng Đạo further up the road that same day. Well, the citadel here was the other major stage in this power struggle. By 1778, the underdog hero Nguyễn Nhạc had driven both the entrenched powers of the Lê and Nguyễn houses (no relation, just an unfortunately common surname) out of south-central Vietnam. After proclaiming himself Emperor Quang Trung—because why not—he needed a suitably imperial seat of power.

He chose the site of Chà Bàn for his center which then became known as Hoàng Đế Citadel. The interim time was a period of the area being opened up for Vietnamese people to move from the north and settle (source). There are records that prior, the Nguyễn clan had a fortification just 1km north of Chà Bàn’s outer wall, but when Nguyễn Nhạc defeated these forces he chose to relocate to the heard of the old Cham citadel. At the Quang Trung Museum, a mural shows an artist’s impression of the citadel during Tây Sơn rule.

After the defeat of Tây Sơn at the decisive naval battle of Thi Nai in 1801, the fortress fell to the Nguyễn forces the very next day. The name was changed to Binh Dinh meaning “subjugated”, this later became the name of the whole province until 2025.

The fortress was left to Võ Tánh and Ngô Tùng Châu to defend and they were soon besieged by Tay Son forces. The siege lasted 14 months. Food ran out and the defending army had to eat the horses and the elephants. Võ Tánh continued to hold out in order to keep the Tay Son army occupied to allow the emperor to conquer Hue. When it became clear there was no hope left, Ngô Tùng Châu committed suicide by drinking poison. After burying his friend and colleague, Võ Tánh locked himself in the Octagonal Pagoda then set it ablaze. Moved by their bravery, the Tay Son commander gave Võ Tánh a funeral and constructed a circular tomb. Both graves can still be seen in the citadel site. (source)

Finally in 1814 a more modern fort was built 5km source which stood as the administrative center of Binh Dinh province until 1930 when it was moved to Quy Nhon City and the age of citadels was over.

After my little picnic in the citadel (with all that history still unknown to me), I stood up, brushed off the bánh mì crumbs and ambled over to Cánh Tiên tower. There was a ticket booth this time but no ticket seller, so I did what any responsible citizen would do: I quietly slipped in through the fence and had a look around. Cham towers are always worth a visit. Their ornate, regal, and mystical forms are like something an explorer in a pith helmet would stumble upon in the jungle in a storybook — even if they do often smell of guano.

As I admired the tower, I noticed another tower perched on a distant hill. Then another. And another. That became the pattern for the rest of the afternoon: visit one tower, spot the next. By the time the sun began to dip, I’d visited four Cham towers and traced a good stretch of this region’s layered past before rolling on towards Tây Sơn District to learn what history could be learned there.

I’d set off to try and outrun heartbreak and found myself drawn to these ancient places. Why am I so captivated by the ruins? Perhaps it’s because their broken walls reflect something inside of me. Or perhaps it’s a feeling that if I can’t make sense of my own story, maybe I can at least trace the stories written on the hills of this wonderful country that I have come to call my home.