I’m experimenting with a new format for my post where all the historical/geographic details will come at the end in appendices.

It was a quiet street in the early morning, almost empty except for a lone man leisurely passing by on an elephant. The great beast padded softly on the tarmac, surprisingly quiet for its size. The rider looked bored — just another Wednesday morning. Around them, the town stirred slowly: weathered wooden stilt houses, smoke drifting from cooking fires, the air already losing the night’s cool. This is Buôn Đôn which has long been a cultural crossroads. Not only Vietnamese, but the indigenous M’nông and Êđê call the town home, and there’s even a small yet significant Laotian community established since the late nineteenth century.

I hadn’t even planned to come to Buôn Đôn. I’d been on the road since dawn, making several stops along the way (including a midday dip in a waterfall). By the time I reached my intended destination — the Champa tower at Yang Prong — schoolchildren were spilling out of classrooms, meandering home on their bicycles and e-bikes. Both I and my moped were plastered in sunbaked mud after kilometre upon kilometre of dirt tracks through the sparse dry forest typical of the highlands.

The ancient temple stood in a pocket of untamed jungle, towering trees filtering shafts of light onto the red brickwork. It’s the last of its kind in the Central Highlands – standing strong and dignified like an elephant. At its base, sticks of incense burned beside candles and small offerings of fruit and bottled drinks, freshly left by locals. Soon after I arrived, a group of schoolchildren came to hangout. They asked the usual English learner questions — “What’s your name? Where are you from?” — then asked me to pose with them for a photo. The tower was worth the journey, but I’d driven an awfully long way, and the sky was already dimming. A glance at Google Maps showed “Buôn Đôn” was a town an hour’s drive south had some places to stay.

After waiting a quarter of an hour in the dark, the owner appeared on a moped with her daughter and unlocked a vacant hut for me. The attic-like single room had three beds, thin plank walls, and textiles in vaguely tribal patterns. You might call it glamping. The first place I’d tried to stay rejected me saying that didn’t host foreigners. I sat on the veranda eating instant noodles, listening to the night chorus of insects and frogs. It wasn’t the most comfortable night — the mattress was hard, and a pair of tree frogs kept launching themselves across the room with loud thuds — but I was too tired to care. So much for glamour.

The hoofprints, the smell of blood, the jawbone — all signs pointed to a ritual animal sacrifice. In Buôn Đôn, the old traditions die hard. Each grave is marked by a sarcophagus-like tomb, topped with a tin roof and flanked at the corners by carved animal figures. A headstone, often bearing a faded photograph, watches over a small wooden offering tray at the front. I counted at least four such graveyards scattered around the town. However, more impressive were the three large mausoleums, each with its own story to tell.

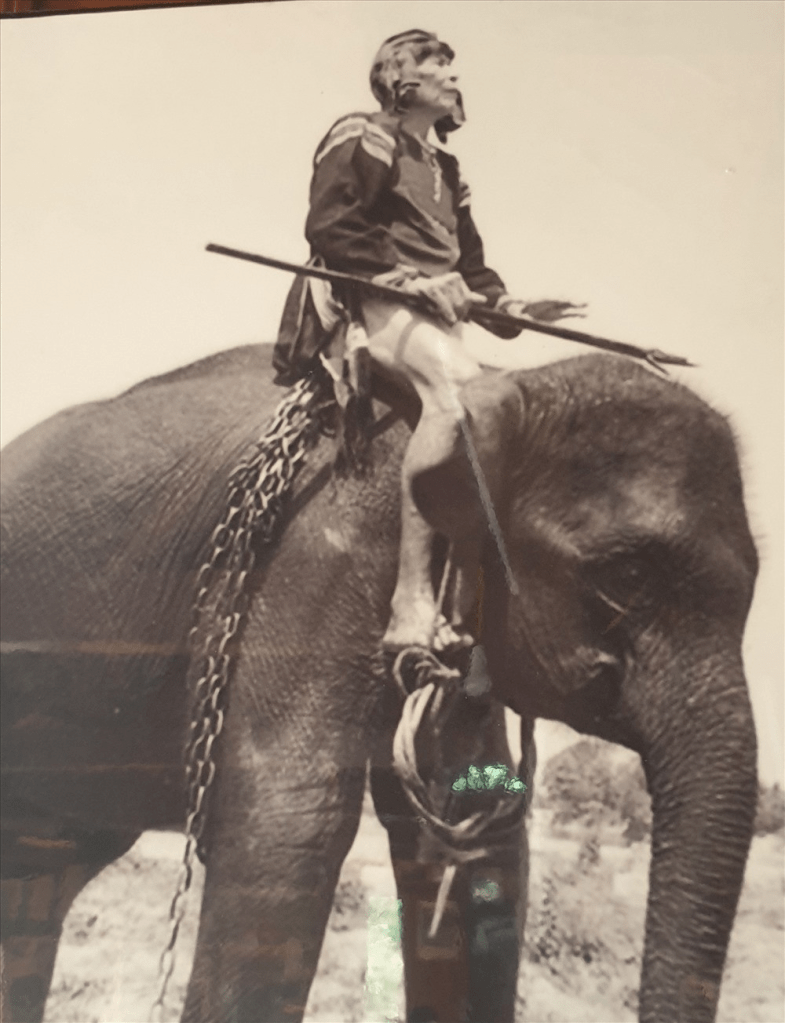

These mausoleums belong to three generations of leaders who held the title Elephant King from the mid 19th century until 2012. Their tombs are striking structures, built in the Lao style rare in Vietnam, with ornate stupa-like structure pointing towards the sky. There is no current Elephant king but their legacy lives on in Buôn Đôn’s enduring association with elephants. Several sites around town still keep elephants for visitors to see, though the days of elephant-back rides, races, and other activities have been stopped because they’re considered inhumane.

I’d set off the morning before hoping to learn about a Champa tower, but I’d also managed to stumble upon the legacy of a dynasty of elephant kings. It was a reminder that the Central Highlands still has secrets to be uncovered — if I ever get the chance.

Appendix A

Yang Prong Champa Tower

Although there are many archeological sites in the Central Highlands from the Champa kingdom, Yang Prong is the only complete Cham tower in the region (Google Maps Link for Yang Prong). It stands just outside the small town of Ea Rốk in north-west Đắk Lắk in a small patch of jungle shaded by tall trees. This contrasts with the Cham towers I’ve visited in Bình Định, which tend to stand exposed on bare hilltops. The canopy made the place cool and pleasant to sit on one of the benches for a while and quietly reflect. Yang Prong in Ede means the tower of the Great God, the god who controls the crops according to local custom.

The tower was built as a shrine to Shiva by King Jaya Simhavarman III (Chế Mân) in the late 13th century. Chế Mân is remembered as the Cham ruler who allied with Đại Việt to repel the Mongol invasion, and later married the Vietnamese princess Huyền Trân in exchange for the territories of Châu Ô and Châu Lý. The union is seen by many as marking the beginning of Champa’s decline.

Sources say the tower was once part of a citadel complex, similar to the one I wrote about at Hoàng Đế but much smaller (source). Fresh offerings of fruit, incense sticks, and candles suggest continuing local reverence. When I arrived at dusk, a group of children were hanging out after school. The site felt like a part of the fabric of the local community.

The Đắk Lắk provincial authorities have expressed interest in promoting tourism to the Yang Prong tower. In my opinion, the site could be enhanced with a path running along the riverbank, allowing visitors to better appreciate the landscape and setting of the monument.

Interestingly, to connect the Champa ruins to the topic of elephant kings, the stele of Drang Lai from 1435CE found at modern day Ayunpa speaks of “Close political ties between the lowlands and highlands led to the integration of the ‘Great king of the Montagnards’ within a territory called Madhyamagrāma, and the vassalage of Śrī Gajarāja (‘King of the Elephants’)” (source). Y Thu may have been aware of a long tradition of elephant kings when he took the title.

Appendix B

Y Thu K’Nul: Elephant King I

The oldest mausoleum in Buôn Đôn is to Y Thu K’Nul and was constructed in 1938. He is reported to have been 110 years old when he died. source, source

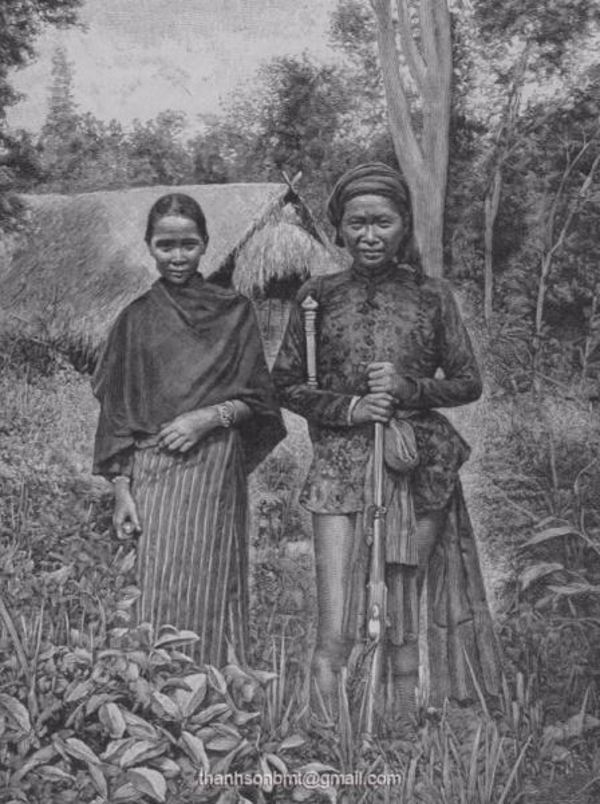

Y Thu K’Nul was a man of the M’nông peoples. He also had an affinity for the Lao people and adopted their style of dress. This is probably connected to the fact there was a budding Laos diaspora in the area at the time (source). In fact the name Buôn Đôn is said to be from Laos (ດອນ) meaning islands, for all the small islands in the area on the river (source).

He was supposedly given the title Khunjunob which according to Vietnamese sources means Rich and Noble Man. He was given this title in 1861 by the Siamese emperor upon delivering a white elephant. I can’t find any source for this that isn’t Vietnamese although Khun (ขุน) is Thai for chieftain.

In 1933 Emperor Bảo Đại visited Buon Ma Thuot where Y Thu arranged for the emperor to be greeted by 162 elephants lining the road. Several photographs survive of this event.

According to historical documents kept at Dak Lak Museum, in the 1900s, when Y Thu was over 70 years old, he stopped participating in elephant hunting, taming and trading and handed over his career to his son, R’leo K’Nu.

He is buried in a mausoleum in Buôn Đôn and his son R’leo K’Nu was later buried next to him. Google Maps Link

Appendix C

Y Prông Êban: Elephant King III AKA Ama Kong

Ama Kông (1910–2012), born Y Prông Êban, was the third and final generation of elephant kings succeeding R’leo K’Nu. His name is well known today partly because of a brand of herbal mens-health tea sold at almost all tourist destinations in Dak Lak. Over his lifetime, he reportedly caught 298 wild elephants.

He was recognised by Hồ Chí Minh for his contributions to the first indo-chine war.

His final hunt took place in 1996, after which he retired to train elephants for Yok Đôn National Park.

He died in 2012, said to be over a hundred years old. His tomb, built in the Lao style, is in the middle of Buôn Đôn. Google maps link.

Appendix D

White Elephants

While researching this article, I kept coming across white elephants. Ama Kong is reported to have captured 3 (source). Y Thu K’Nul also captured one which he gifted to the Vietnamese Emperor Bảo Đại (source).

Why do the sources mention about white elephants? Well owning white elephants is a symbol of royalty in south east asia. The tradition comes from Buddhism where white elephants are associated with Śakra, the ruler of the Trāyastriṃśa Heaven. They are so important that the Burmese-Siamese War of 1563–1564 was fought over white elephants.

I was surprised to learn white elephants are not actually white. They may be pink or have pink patches. In Thailand, white elephants are “graded” and lower grades are often rejected by the king.

According to the experience that Mr. Ama Kong passed on to his son, to distinguish white elephants from normal elephants, one can only look at their eyes and tusks. White elephants have blue eyes, and pink tusks. Herds containing white elephants are often very large, they are very gentle, and especially white elephants are always in the center. – on Khăm Phết Lào son of Ama Kong

Of course we have the idiom “white elephant” this is from the convention in Thailand where the king will give lower grade white elephants to people who have annoyed him. The sacred animals are not allowed to work but must be looked after at great expense to the owner.