I’ve always been curious about the dramatic storms you see in films like cyclones and twisters. What is it like to experience one first hand? Well, I ended up being right at the epicenter of a tropical typhoon. Here’s my story.

Steve, a tall Englishman with cropped grey hair and the air of someone who’s seen it all, runs a small beachside resort of bamboo huts and a backpacker dorm just outside Quy Nhơn City, central Vietnam. We’d arranged that I’d come down to help out for a bit—hosting guests in exchange for a bunk, meals, and all the beer I can drink.

But when I arrived, there was a spanner in the works. Steve was fretting over the forecast. He’d been in Vietnam twelve years and had seen enough storms to know when one meant trouble. “It’s going to be the worst since 2017,” he told me. For me, this was a bit of an adventure but for him, his whole livelihood was at risk. The forecasts showed the storm would make landfall almost exactly here – Quy Nhơn was to be the epicenter.

He didn’t like having guests around in that kind of weather—too risky if something happened or needed to reach a hospital. He suggested I find a hotel in town. I took the hint and went on Wednesday, choosing somewhere a few streets back from the seafront (it seemed sensible).

At check-in, the staff warned me: There’s a storm coming.

I said I knew.

There will be no power tomorrow, they added.

That was fine by me.

That evening, I went to the supermarket to stock up on supplies. There was a buzz of urgency like going to the supermarket on Christmas Eve. The crisp and instant noodle aisles had been stripped bare. I needed things that wouldn’t require cooking or refrigeration—fruit, bottled water, chocolate, and a few packs of dried squid and “Peperami” for protein.

Afterwards, I stopped by 69 Pub, run by my friends Kevin and Trinh. There I bumped into one of the Pleiku old boys, and we drank late into the night. He was planning to drive back to the highlands the next morning to visit Kevin, and invited me along. But the idea of taking the infamous An Khê Pass in a typhoon didn’t appeal. Better to hunker down and wait it out.

Outside, workers were busy cutting branches from trees and tying trunks to buildings. The news reported that 140 people had died when the same storm swept through the Philippines. From my hotel window, I looked out over a patchwork of tin roofs weighed down with a variety of things – tires, polystyrene crates, binbags full of water.

By eight in the morning, it looked like a normal rainy day outside. The wind was nothing alarming yet—just the usual “better to curl up with a book” kind of weather. The housekeepers knocked on my door. They were going home after finishing their round and handed me extra bottles of water and a fistful of instant coffee sachets.

By ten, the food stalls had all closed up. A few people still hurried along the pavements. I made a pot noodle in my room and was reminded of Saigon during the covid-19 lockdowns. I realise for the first time that ever since then, I’ve hated staying indoors. I always have to get out and go somewhere every day. Sometimes I hop from cafe to cafe all day long. I sit back on the bed and mentally prepare to stay put like back in lockdown.

By noon, the rain was slanting hard against the windows. The building groaned under the wind. The afternoon light was dim like midwinter, the clouds were heavy. There was still some traffic, even a few motorbikes out but no one was out on foot now. I ate snacks, read, and watched YouTube.

At five a friend in the Pleiku police called me to tell me that Quy Nhơn was planning to turn the power off soon. I decided to eat my second pot noodle while I still could but the power went before the kettle boiled. The city was plunged into the gloom of the fading light filtered through the storm. My first thought, “do I have enough phone battery?” The wind was now howling between the buildings, flinging debris across the street. It sounded like an approaching tube train that never arrived. A shop sign scraped along the road as if it had a mind of its own. I could feel the window pulsing under the pressure. Suddenly, a man walked past in shorts and flip-flops, no shirt – only in Vietnam! Bits of roofing came loose above me.

I watched as the building opposite, the one with binbags full of water as ballast. The bags were popping, emptying then flying up into the air as if being abducted by aliens.

At seven it all suddenly stopped. After hours of steady escalation, the silence felt unreal. I wondered if we were in the eye of the storm. I’m anxious to know if the storm will come back. Outside, people were out with torches, small coordinated gangs of men moving with purpose—they were quickly moving the large dangerous pieces of debris into basements.

When I opened the window, a strong smell hit me. It was part sea breeze, part earth after rain, and part something electric, like licking a 9 volt battery. Then the wind returned—as suddenly as it had stopped—I quickly shut the window. Down in the street, a single torchlight darted past, the point of light wobbling as a man sprinted across the wind.

I lay down alone in the darkness, the bed shaking as the whole building rattles with the wind. I thought of Steve at the coast, his huts facing the wind, and wondered how they were holding up.

I woke at six to stillness and clean blue skies. There was no power and no phone signal. I decided my lockdown was over. I slung my camera over my shoulder, then hesitated—was it crass to photograph the wreckage?

Like many modern hotels, mine had no guest stairwell, and with the lift dead, I took the outside fire escape to the lobby. The front door was barricaded with sofas and tied shut with rope, so I slipped out through the basement car park, ducking beneath a screen door which someone had bent just enough to get under.

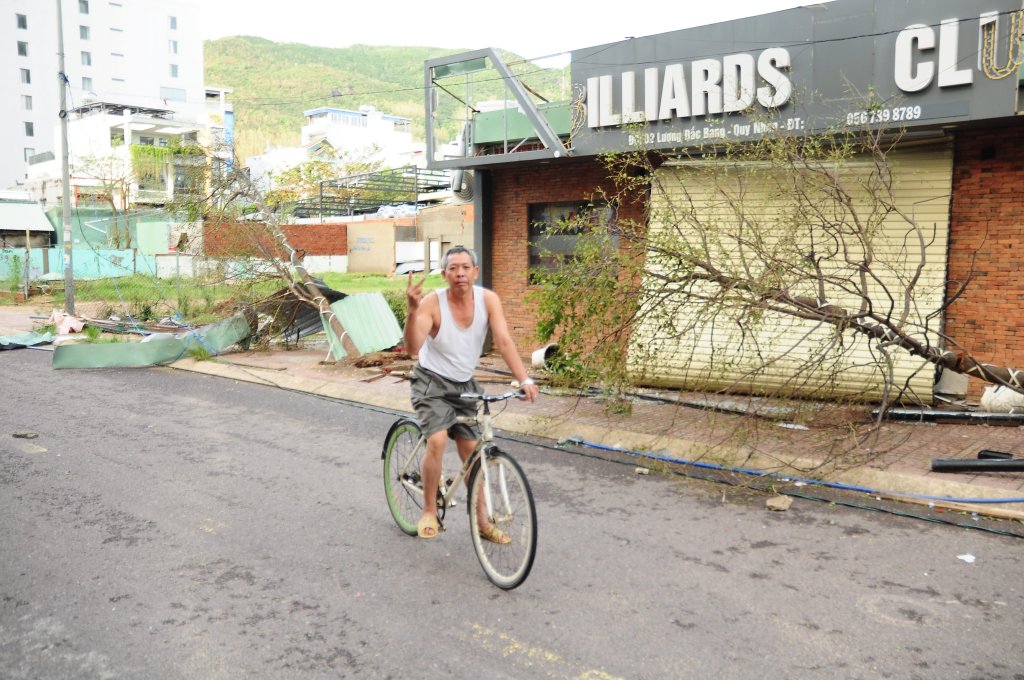

I needn’t’ve worried about the camera. If anything, they encouraged me. “Take a photo of that!” one man called, pointing to a billiards parlour reduced to rubble. Another insisted I take his portrait. This area has only hotels and restaurants so perhaps people felt no privacy was being invaded.

The street looked like a bomb hit. Several buildings had collapsed roofs, some are just piles of splintered wood so I can’t even tell what there were before. Many of the big hotels have windows smashed out. Street lights, trees and telegraph poles lay across the tarmac. Power cables dangled all over the road like vines in the jungle.

A group of university students ran past, laughing, clutching coconuts that must have blown from some public trees. Many of the men I passed were out inspecting the damage, hands on hips, giving me the same look that seemed to say, “Would you look at that.” There was a strange sense of camaraderie, as if we’d all survived something together.

I wandered back down to 69 Pub, where I’d been drinking two days earlier, to see how it had fared. The front was unrecognisable: the sign’s letters had vanished, trees were down, and the air-conditioning unit dangled by its pipe. But the squat building with its rolling shutters looked largely intact from where I stood. It felt strange—two nights ago there was laughter and music, now it was just silent.

“Yeah dude… fuckin sucks,” Kevin texted back when I sent him a photo.

By seven, the city was alive with activity: shop-owners swept, some street cafés had open, an old lady was selling something fried for breakfast from a grill on the street. Sirens blared as police and ambulances went past at regular intervals. The army were clearing the hospital. Quy Nhơn was already piecing itself back together. I was amazed by the resilience of the people here.

With schools closed, there are gangs of kids out enjoying the seafront. The road along the seafront has about a foot deep in sand making a brand new beach for them to play in as motorbikes gingerly drove by – the actual beach was covered in debris and litter. One of the parks along the promenade has filled with water making a temporary swimming pool, kids were splashing around having a whale of a time, some even have floats. It reminds me of the day we got sent home because of a storm when I was in secondary school in England. What frightened adults felt like adventure to us kids.

By late afternoon, electricity flickered back to life in some small parts of the city. Most of Quy Nhơn remained dark, though, lit only by the flow of mopeds. I found a different hotel with electricity and text Steve

“How’s it going?”

I get one word in response: “Catastrophe”.

The next morning, as I ate phở for breakfast, a convoy of huge military flatbed trucks thundered past — maybe twenty in all. Later, I saw them carting away fallen trees, street lamps, even heaps of sand to a builders’ yard outside town. I guessed that must have been the sand that turned the coast road into a beach.

When the petrol stations reopened, I filled up and drove back to Steve’s resort. The first thing I saw was the staff dorm where I’d been sleeping. There was no roof. The Vietnamese staff were squatting outside the guest dorm, which was luckily undamaged.

“Was anybody hurt?” I asked.

“No… oh yes, Steve.”

“What happened?”

“He’s got a broken heart.”

I found Steve with a towel over his head, salvaging furniture from a roofless room. He told me I could consider myself officially dismissed from my volunteer role.

You can view more photos here: https://photos.app.goo.gl/tCNZ4c9YY2A1pegSA