I stopped to take a photo of the Cham tower between the houses and an elderly lady struck up conversation. She pointed to the other side of the road and said I should take a photo of that house too.

I politely asked her why.

She replied matter-of-factly “The storm blew the roof blew off”.

Bình Lâm is a quiet village sat as an island surrounded by flooded rice paddies, the roads rose just above the placid water like causeways. Villagers went about their business with no sense of hurry. It reminded me of the type of lacquered painting of rural scenes you see in many Vietnamese households.

Most Cham towers in the province stand on solitary hilltops, but in Bình Lâm a brick spire rises right in the middle of the village, hemmed in by houses.. As I wonder around and looked inside, taking photos and reading the information board, a grey-haired man is sweeping his front yard just meters away. The signs say this is the oldest surviving tower in Bình Định, built sometime in the 10th or early 11th century (source) but that’s not the only reason it’s interesting to me.

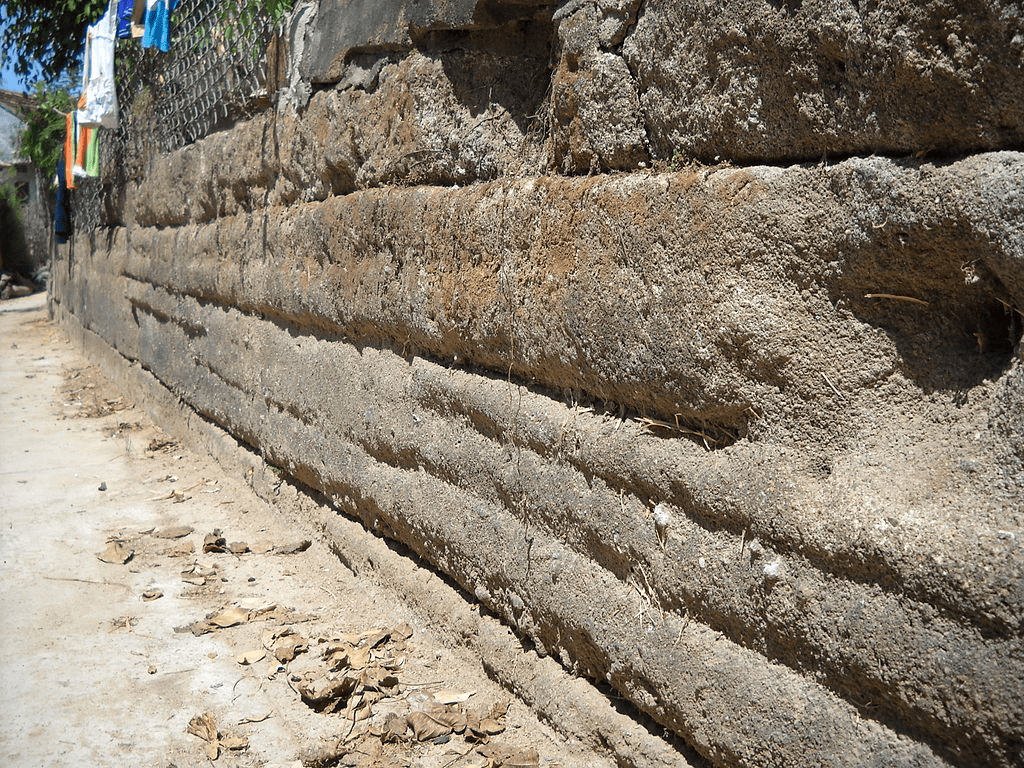

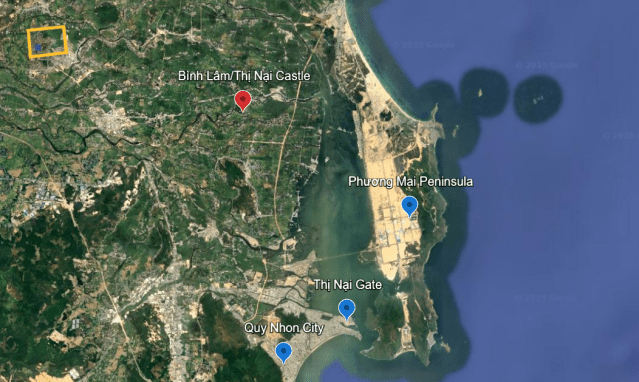

I’d read online that the tower once sat in Thị Nại Castle and I wanted to see if I could see any traces of the fortifications because Wikipedia has a photo of a section of wall. In the days of Champa, the castle guarded the capital of Vijaya from attacks by sea, standing downstream near the mouth of the Kon River as it emptied into Thị Nại Lagoon. Bình Lâm is on an island where the river’s branching distributaries form a natural moat — while the lagoon beyond formed a vast defensive basin enclosed by the long, mountainous Phương Mai Peninsula, with its narrow southern entrance called the Thị Nại Gate.

Across the centuries, the lagoon has witnessed some of the defining moments of Vietnamese history, the sort that fill the chronicles with all their grim detail. If Thành Hoàng Đế was the capital of two kingdoms, then Thị Nại lagoon became their graveyard. Yet none of that weight felt apparent as I drove around the area. The only hint of history is the Bình Lâm tower, faintly visible from the road between Quy Nhơn and Cát Tiến, a resort town known for its giant hillside Buddha. Even the Quy Nhơn Museum understates the history, but a few nineteenth-century cannons from the naval battle that ended the Tây Sơn dynasty stand quietly in the front yard giving a hint about the history.

Here is a 1932 poem by Trường Xuyên

Thi Nai was once a battlefield, the ups and

downs of the world were the result of many dynasties…

The mountains and clouds were billowing where soldiers were fierce,

The sea of red blood had not yet dissipated.

The cold geese played with the emperor’s mirror in

the Phuong Mai forest, covering the wounds of grief.

Sadly, I look back at the scene,

Layers of cars bustling the streets!

The late afternoon light was weak through the cloud cover, at least I didn’t need to worry about sunburn. I didn’t manage to find any trace of the castle in the end other than the cham tower but it was nice to drive around a quiet village and enjoy the scenery. I rode back down the windswept Phương Mai Peninsula, the wide roads half-buried in sand, giving it a desolate feel. Crossing the long Thị Nại Bridge that today stretches across the middle of the lagoon, I could see the city’s high-rises in the distance, with the odd boat drifting quietly across the calm lagoon.

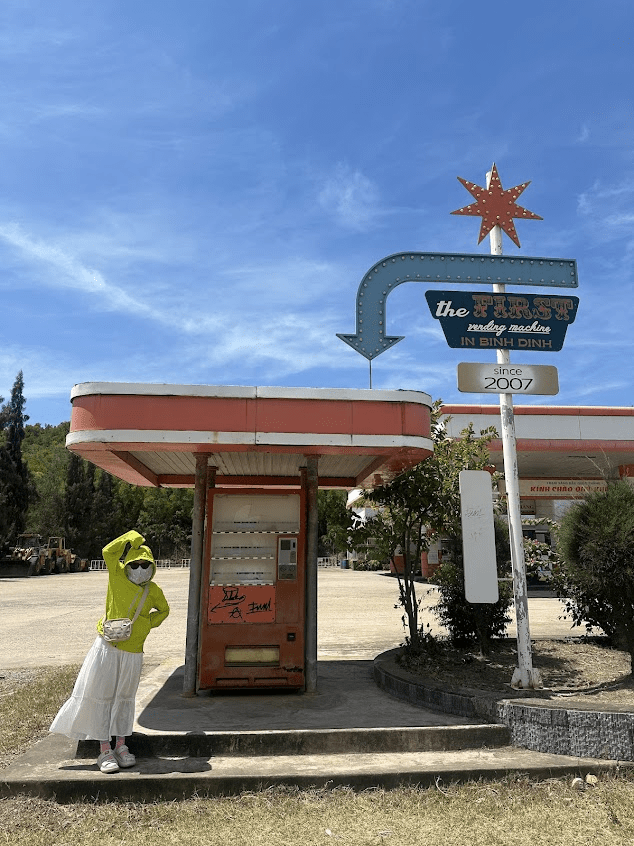

But I had one final stop to make. It was at my friend Brad’s all-time favourite tourist attraction: the First Vending Machine in Bình Định. Erected in 2007 shortly after the bridge was opened — wow what a venerable relic! It even has a light-up arrow sign, like something out of an American movie. To my dismay, it too had been blown over by the same storm that had lifted a roof off a house in Bình Lâm. Let the chroniclers record one more fallen hero on the banks of the Thị Nại Lagoon.

Appendix

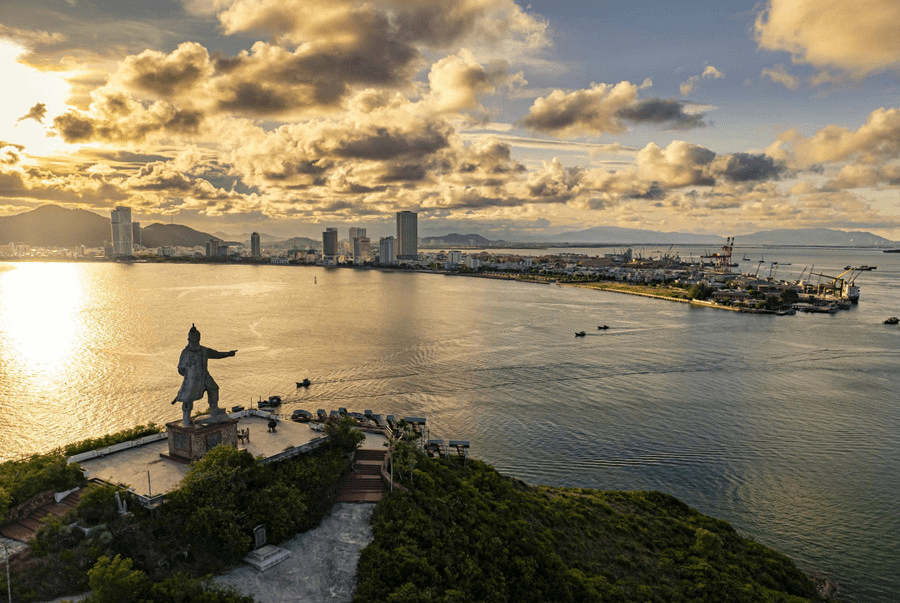

Thị Nại Lagoon has borne witness to some of the defining moments in Vietnamese history. One such event took place in 1284, when a Mongol fleet of over a thousand ships arrived at Thị Nại and took the castle (source). However, unable to make further gains in Champa, the Mongols withdrew and headed north to challenge Đại Việt — where Emperor Trần Hưng Đạo crushed them in battle. Now, a 16-metre statue of Trần Hưng Đạo stands on the tip of the Phương Mai Peninsula watching over the Thị Nại Gate.

Another major event happened two centuries later, in 1471. According to the chronicles, Vietnamese emperor Lê Thánh Tông attacked this castle, beheading a hundred defenders before taking the capital of Vijaya thirteen kilometres inland. From then on the area would be firmly under the control of the Vietnamese — a major milestone in Vietnam’s southward expansion that shaped the country’s modern borders.

On the 27th, the king himself [Lê Thánh Tông] led a large army to attack Thị Nại castle, beheaded more than 100 people. (Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư pp. 1383)

Jump ahead to the early 19th century and Vietnam is torn apart by the civil war between the Tay Son and the Nguyen Lords. Here was The Battle of Thị Nại — a naval battle that took place in 1801 — considered to be the decisive victory for the Nguyen dynasty. The Tay Son lost around 20,000 men and almost the entire fleet: 1,800 ships and 600 cannons. Some cannons have been recovered from the lagoon and are displayed outside Quy Nhơn museum, tangible reminders of the fierce history the calm waters hide.

The enemy held the fortress and fought fiercely. From the hour of Dần to the hour of Ngọ, the sound of guns resounded throughout the sky, bullets flew like rain. … Duyệt [Lê Văn Duyệt] swore to offer his life, waved his troops to charge forward, and at the right moment entered the sea gate, using fire torches to attack the enemy’s flagship. The Tây Sơn army was broken and many died. Dũng [Võ Văn Dũng] was defeated and fled. The Tây Sơn boats were almost all burned. Our army then held Thị Nại Gate. People praised this battle as the greatest martial art – Đại Nam thực lục

In 1885, the castle was occupied by the French, then, some time during the reign of emperor Thành Thái (1889-1907), the castle was demolished and the area turned into farmland. Not needing the natural defenses, the modern city of Quy Nhơn continued to grow outside the Thi Nai gate for easy access for shipping vessels and fishing ships alike, as well as a beautiful beach-front attracting tourists.