When I first came to Tuy Hòa, I had vague ideas about funding my travels by writing online. This was before ChatGPT, when copywriter might have been a viable option. I used this blog to practise, read a few guides, and produced some quite bad content including a piece about “hidden gems in Vietnam”, which I’ve deleted since out of embarrassment. At the time, I spoke about hidden gems with the assumption all readers knew what it meant: an excellent destination tucked out of sight, unspoilt by tourists or commerce. I even described Quy Nhơn as a hidden gem, which now makes me chuckle, given how touristic it feels compared to places like Pleiku. The longer I travel, the less certain I am that people mean the same thing when they use the phrase at all, or that such gems exist in the way travel blogs like to imagine them.

The topic resurfaced by coincidence over the new year. After an action-packed Christmas in Pleiku, I met an old friend, Pierre, in Buôn Ma Thuột, who pulled together a trip with several people I’d never met. We went first to Nha Trang for the new year fireworks on its crowded promenade, then on to Tuy Hòa. Four of us ended up travelling together, loosely connected and still feeling one another out. During some idle small talk, one expat, Akil, asked me which beaches were good and still unknown given I’d visited Tuy Hoa already. I admitted I didn’t really know. He said, “Oh, so you’re not much of an explorer then.”

The remark stayed with me. For Akil, exploration means beaches, viewpoints, unexpected vegan restaurants. Are they hidden gems? I think some people would agree they are.

For me, exploration usually takes a different form. I’m less drawn to beautiful places and more to historical spots — to places that help explain how a region became what it is. Museums, communal houses, half-neglected shrines by the roadside. Places where the reward is understanding rather than sensory.

The following day, while everyone else was off at a beach I returned to the provincial museum, which I’d already visited once before. This time, I could read the Vietnamese-only signage with far greater ease, and I have a better grasp of the nations history. Names that had once meant little — Lê Thánh Tông, Quang Trung, Gia Long — now connected to chronicles I’m getting familiar with. After that I went to find the tomb of Lương Văn Chánh and had a peaceful afternoon driving across the countryside and resting on a bench in the shade as the local children were playing.

In the museum I had noticed references to several nearby historical sites I’d never visited: a small cluster of đình and đền scattered around the Ba River estuary (communal houses and temples respectively). So the next day after the others left Tuy Hòa, I rented a motorbike and set out alone to find them. I’ll put details of all the stops I made in the appendix. Most were easy enough to reach, sitting quietly in villages, but sign posted and listed on Google maps. Then there was one that refused to be located at all.

Đình Phú Sen had no pin on Google Maps, no photographs, no digital footprint. Armed only with a photo from the museum and the name of the commune, I rode into the village and stopped at a small bakery, buying a few cakes as an excuse to ask for directions. I followed the guidance slowly, scanning for anything that looked older than its surroundings.

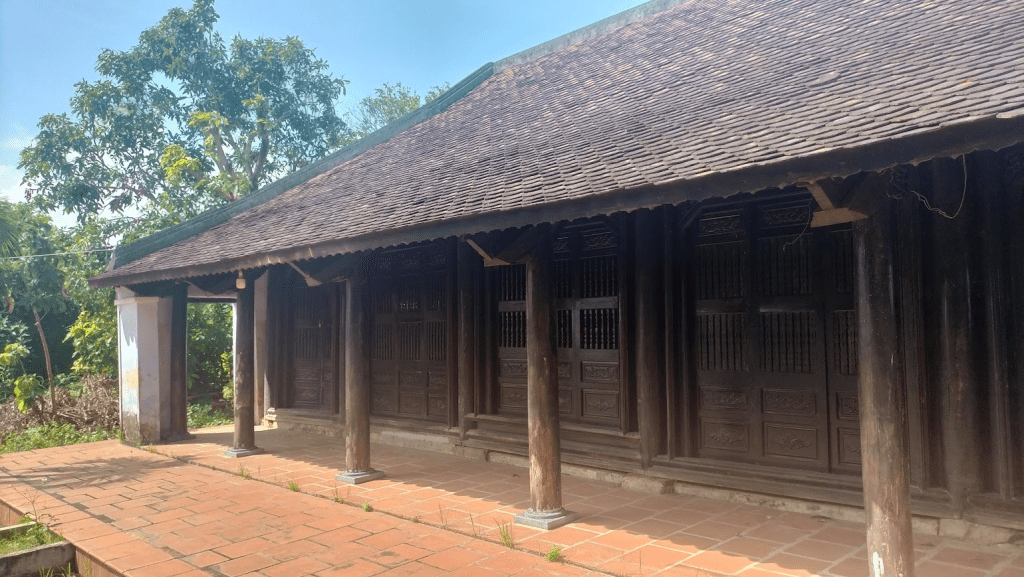

I nearly passed it. What caught my eye first was a family gathering under a gazebo. Behind it, half-hidden among trees, stood a low, weathered structure. Outside, a group of children of mixed ages were loitering. “We’re a lion dance troupe!” they told me and eagerly showed me their drums and cymbals. When I asked whether this was Đình Phú Sen, holding up the museum photo, they erupted with excitement and told me it was.

The building was in a squat traditional style, not so old – an inscription suggested the modern building was built in 1995 but the site dates back to one of the earliest Vietnamese settlement in the area. Photos were taken, then selfies, then more selfies. I gave them the cakes. Before leaving, I added the location to Google Maps. I’d actually driven this way before on the road from Pleiku to Tuy Hòa but hadn’t noticed the building at all, it meant nothing to me.

On the ride back to the hotel, I kept thinking about hidden gems. It’s funny that if we search for them: type the phrase into Google and the results are, by how search engines work, the most popular places of all. The term promises reward without crowds, yet anything that reliably delivers a good experience will eventually attract people.

For me, a hidden gem is a place you find by following your most niche interests. It could be a place that you can’t find online, only in a single photo in a museum then you set out to find. Because it takes you off the beaten track and forces you to have interactions you wouldn’t otherwise have. It’s not about spectacular places but the unique experience of that outing: people you happen to meet, the things you learn, and the small things — sharing a few cakes.

Appendix: How Phú Yên became part of Vietnam

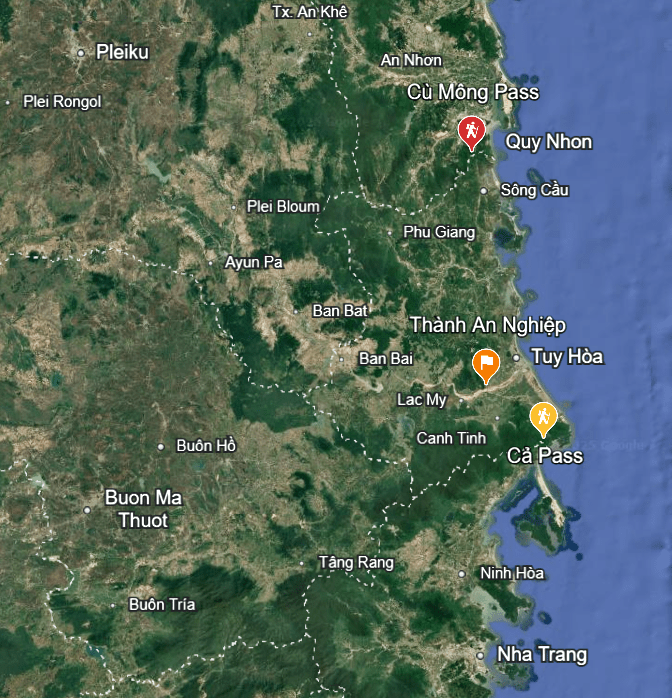

In 1471, The Vietnamese Emporer Lê Thánh Tông defeated the Cham Kingdom of Vijaya in Quy Nhon. Annexing the area of Vijaya (today Gia Lai) into Dai Viet. Tuy Hoa sits in the area the Cham people called Ayaru which is bordered to the north by the Cu Mong pass and to the south by the Ca pass, while on the east is the coast and the west is the rugged highlands. It was a vasal of Kauthara (with the capital at Nha Trang). So, after pacifying Vijaya, Lê Thánh Tôn created an independent buffer state in Ayaru which they called Hoa Anh (source).

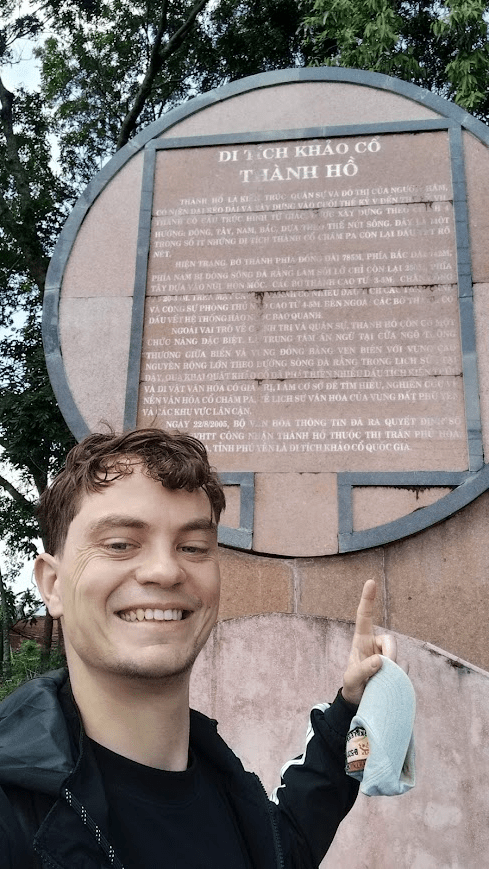

Thành Hồ (AKA Thành An Nghiệp)

The death of Lê Thánh Tông would be the start of several centuries of Game of Thrones style political instability which would not end until after the Tay Son wars. In the late 16th century, about 100 years after the creation of Hoa Anh, Nguyễn Hoàng was the governor of the most southern provinces of Dai Viet down to the Cu Mong Pass. He was a rising star against the backdrop of Game of Thrones style political instability where the Le, Trinh and Mac houses were vying for power, he emerged to establish his own clan: he became the first of the Nguyễn Lords – who would go on to rule South Vietnam for centuries, later being the last dynasty of emperors of Vietnam.

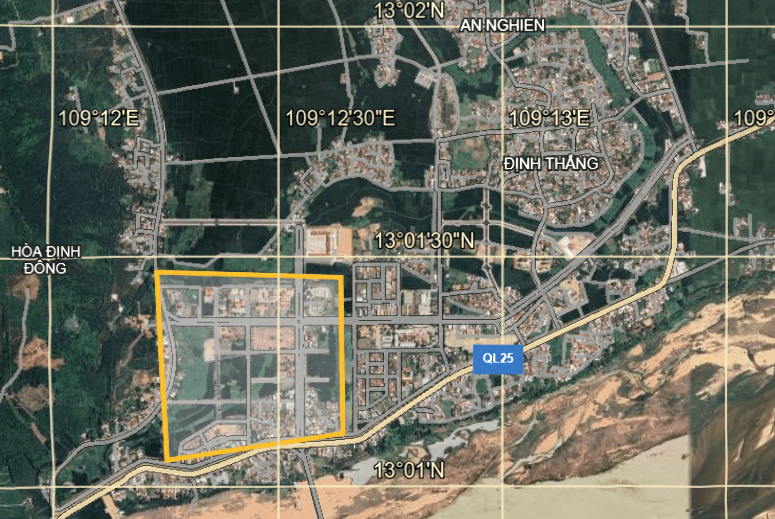

In 1578, in response to an attack from Champa, Lord Nguyễn Hoàng asked his general Lương Văn Chánh to lead an army into Phú Yên, besieging and capturing An Nghiep citadel (Thành Hồ/Thành An Nghiệp) located in Phu Hoa district , west of present-day Tuy Hoa city.

The citadel area can still be visited for free but there is not much to see (maps). The citadel was roughly square with sides of 785x742m and the walls were 3-5m tall. The earth ramparts are still very clear and some brickwork is visible. The moat is still very much there. The site is marked with a huge stele.

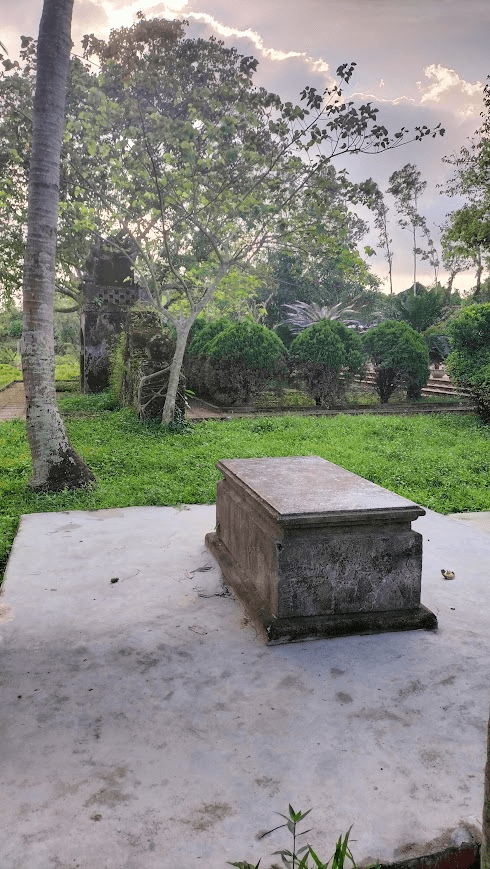

Đền thờ Lương Văn Chánh

If Phú Yên had to pick a founding father, I suspect the locals would choose Lương Văn Chánh; the general who took the citadel.

Having pacified the area, in 1597, Lương Văn Chánh received a decree from Nguyễn Hoàng to bring about 4000 Vietnamese migrants to settle the area. This is a major milestone in bringing the area into the fold of Vietnam and is what Lương Văn Chánh is most remembered for today.

After his death in 1611 Panduranga were able to bring Ayaru under their control under the command of King Po Nit (his Wikipedia page is quite interesting as it contains European accounts of Champa). Nguyễn Hoàng sent the ethnic cham general Văn Phong to push Panduranga out of the area. They swiftly succeeded and after that, the Hoa Anh/Ayaru area was established as Phú Yên prefecture and would from then on always be part of Vietnam.

Lương Văn Chánh’s tomb is at shrine in Hoa Tri where he is worshiped as the village protector deity (maps). It is surrounded by a peaceful green garden area. The drive was lovely, skirting Chóp Chài mountain and across rice paddy causeways. When I arrived, some teenage girls were wearing ao dai and taking photos while some small children were playing. There is an old wall with a traditional gateway and the tomb itself is clearly visible. I think it’s well worth a visit.

Lẫm Phú Lâm

Lẫm Phú Lâm is an old rice granary dating back to the early 17th century (maps). It sits in Phú Lâm village on the south bank of the Ba river estuary. Besides its function as a storage facility, the “lẫm” also served as a place of worship for the village’s ancestors. Since 1945 Lẫm Phú Lâm no longer serves as a storage facility but is purely a place of worship for the local ancestors, one being Huỳnh Đức Chiếu, one of the founders of the village. It is also used for the worship of Cham goddess Thiên Y A Na aka Po Nagar. (source)

Đình Phú Lễ

Phú Lễ communal house was established in 1708 (maps). It is in the village of Phú Lễ near Phú Lâm, with an entrance squeezed behind a local school. There, they worship a water god and store some interesting royal decrees. (source)

Others

I also stopped at Đình thôn Phong Niên (maps) and Đình Phú Sen (maps). They were very picturesque and worth visiting but I can’t find any historical information on them. I missed Đình Vĩnh Phú which was also mentioned in the museum.