While researching the story of Mereyna, I stumbled upon another curious episode featuring some of the same characters caught up in a rather different affair with the Sedang people—this time, a decade later. The deeper I dug, the more it became clear that this story deserved its own blog post.

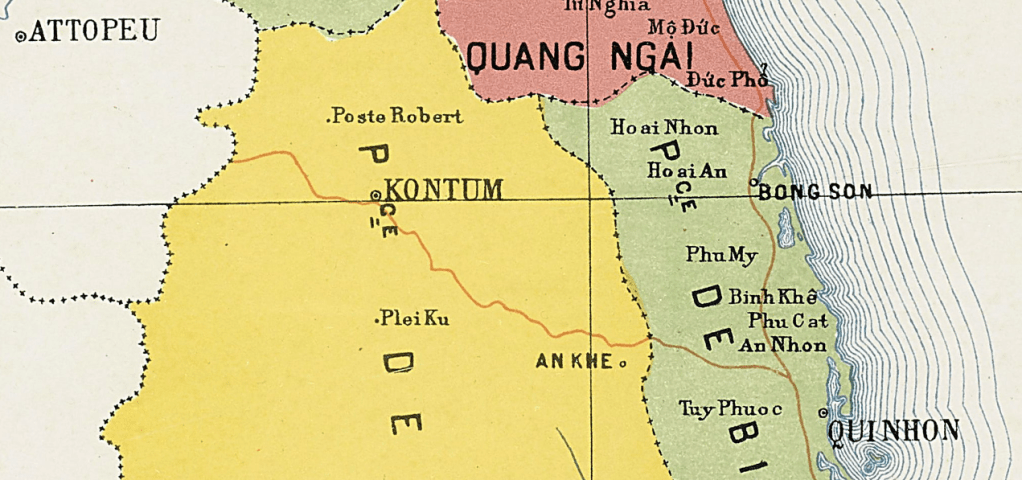

A place called Poste Robert kept popping up in the records. If you glance at a map of Vietnam from that era, you’ll find it marked just north of Kon Tum city, an odd name to see in the heart of the Indochinese mountains. Why is there a European sounding place name in the middle of nowhere? Naturally, I couldn’t resist the urge to dig deeper and also couldn’t resist taking a trip to see the location for myself.

After the Meyrena affair in 1889, the French were keen to assert control over the region. A large enough force was brought in to try to bring the Sedang territory firmly under French rule. The Sedang, of course, were far from thrilled by this development. Their submission, as it turns out, wasn’t as easily won as Meyrena would have had people believe. They opposed the French presence vehemently, and tensions flared over the construction of roads and the increased numbers of outsiders.

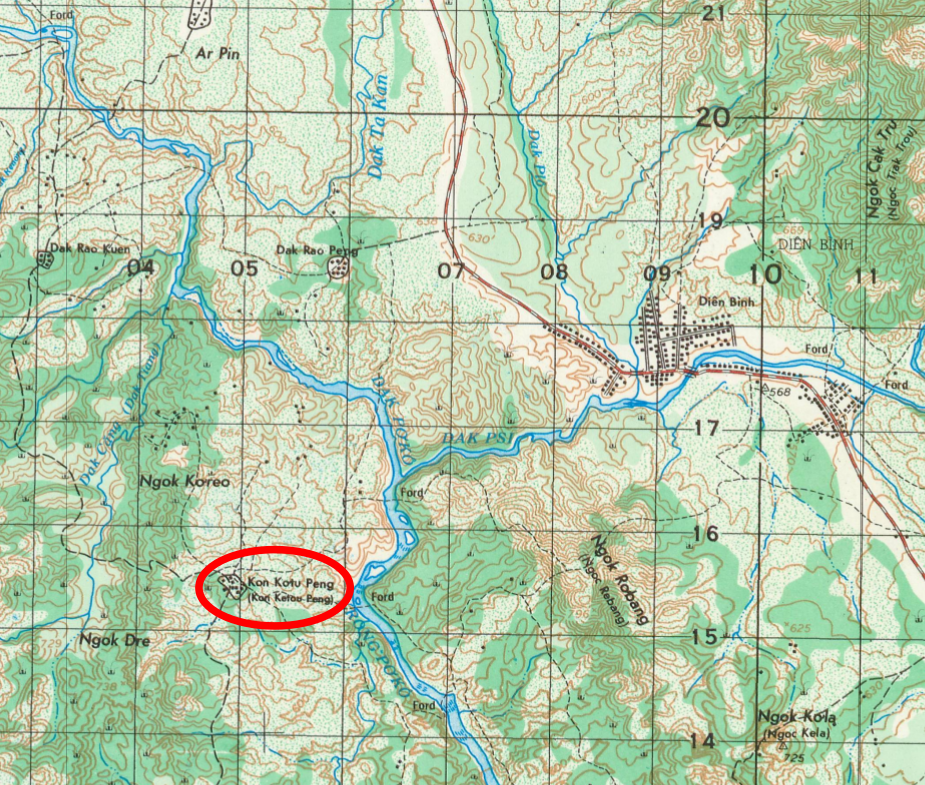

In 1901, a militia commander named Monsieur Robert was sent to establish an outpost near the confluence of the Poko and Psi rivers at a place called Kon Ketou. His task was straightforward enough: protect French interests and maintain some semblance of order between Attopeu and Kon Tum. Kon Ketou sat just 8km north of Kon Gung where the Meyrena episode had taken place a little over a decade before.

By all accounts, the Sedang were not pleased. The post disrupted routes they’d long used for trading commodities with the Jrai people to the south – these commodities were usually taken from the inhabitants of Quang Nam and Quang Ngai by force. Grumpy about this interference, some Sedang leaders decided it was time to remove Robert and his militia from the picture altogether.

Robert, aware of the tension, was warned of a potential attack and set up a guard. Thinking that no one would dare strike in broad daylight, he had the guard keep watch all night. So it was that on the morning of May 17, 1901 he dismissed the guards who had been on night-watch. That decision would prove fatal. At around 9 a.m., a group of roughly a hundred Sedang warriors launched a surprise attack. The post was caught with it’s pants down, and chaos ensued. In the melee, Robert was stabbed twenty times with spears before the attackers melted back into the jungle.

Enter Father Pierre Irigoyen—a name that might ring a bell from the Meyrena episode. He too had caught wind of the plot and, alongside Father Emile Kemlin, another missionary stationed nearby in Dak Drei, made a desperate dash to warn Robert. Unbeknownst to them, it was already too late. When they arrived later that evening, they followed the sound of gunfire through the darkness and found the surviving militias, who had already placed Robert on a stretcher, gravely wounded. Father Irigoyen took charge of the group and led them safely back to Kontum. Sadly, Robert’s injuries were too severe. Despite the best efforts of Father Guerlach, who treated him upon their return, Robert succumbed to his wounds.

The French, undeterred, rebuilt the post later that same year and named it Poste Robert in honor of the fallen commander. For a time, the name appeared on maps of the region, though by the 1970s, when the Americans took their turn mapping the area, it had vanished. Interestingly, the Americans followed the same tradition of naming military places after fallen soldiers, as seen with Camp Holloway in Pleiku City.

The incident was far from the last time the Sedang would show their dissatisfaction. In the years that followed, they launched several more attacks, including repeated raids on Father Kemlin’s residence in Dak Drei. These strikes were among the earliest signs that the Montagnard people wouldn’t be easily subdued by this western powers. The so-called “pacification” of the region would continue to drain French resources for years to come—stories I’ll explore in future posts—culminating in the Montagnards getting their final revenge at the battle of Mang Yang Pass.

For the purposes of this blog post I decided to visit the confluence of the Poko and Psi rivers, even though the precise location of Poste Robert is unknown. It was too tempting a geographical outing to pass up. It was about an hours drive out of Kontum by moped. There’s a Rngao village near the confluence, perched on the same west bank where Kon Ketou once sat. Upon arrival, I spotted the nha rong, a traditional communal house that stood proudly in the village. As I wandered about, a group of local kids gathered around to peek at me, their curiosity mixed with a hint of fear at the sight of a strange foreigner.

To break the tension, I decided to entertain them by pretending to be a zombie, and their laughter filled the village green, easing the initial awkwardness. With spirits lifted, I left my bike behind and made my way down to the riverbank, scrambling through fields and a rubber plantation as I went.

There was, of course, no trace of the French post. Nonetheless, it was easy to imagine the scene over a century ago when tensions ran high between the French forces and the Sedang people, with this peaceful riverbank serving as the backdrop to so much history. On the southwest bank, a round hill rose like a quiet sentinel. As I squatted in a bamboo thicket and looked across to the hill, I imagined smoke curling up from behind a wooden stockade while Sedang warriors, perhaps in this very spot, crouched in the undergrowth, planning their assault.

My adventure took an unexpected turn when I got a nasty bite from a centipede, a sharp reminder that this land, despite the rolling fields, hasn’t quite surrendered to the encroachments of civilization and still has surprises from its wild past. Limping back to my bike, I struck up a conversation with some locals who eyed me with a mix of curiosity and caution. I was particularly taken by the village’s charm, where many houses—though they were the typical modern brick bungalows found throughout Vietnam— sported extensions crafted from woven bamboo.

What struck me most about when researching this post was how a simple curiosity over a strange name on a map led me right back to the familiar names of Irigoyen and Guerlach. It’s a reminder of just how deeply these missionaries were woven into the fabric of the region’s history, their influence reaching far beyond the confines of their religious work. It leaves me wondering what adventure their mark on history will lead me on next.